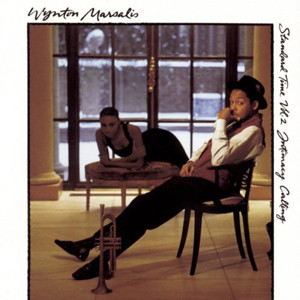

Standard Time, Vol. 2 - Intimacy Calling

Interpreting classic ballads by the Gershwins, Rodgers and Hart, and Thelonious Monk, among others, and his own “Indelible and Nocturnal,” Wynton explores how intimacy calls lovers not just to romance, but to the thrill of mutual self-discovery. Joining him on these late 1980s sessions are Marcus Roberts on piano, Todd Williams and Wes Anderson on saxophones, Reginald Veal or Bob Hurst on bass, and Herlin Riley or Jeff “Tain” Watts on drums. Among this recording’s many treasures, don’t miss Wynton’s powerful muted trumpet work on “When It’s Sleepytime Down South,” “Indelible and Nocturnal,” and “Lover.”

Album Info

| Ensemble | Multiple Ensembles |

|---|---|

| Release Date | March 26th, 1991 |

| Recording Date | September 1987, August 1990 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | 468273 2 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| When It’s Sleepy Time Down South | 5:11 | Play |

| You Don’t Know What Love Is | 6:22 | Play |

| Indelible and Nocturnal | 4:12 | Play |

| I’ll Remember April | 8:35 | Play |

| Embraceable You | 7:13 | Play |

| Crepuscule With Nellie | 3:04 | Play |

| What Is This Thing Called Love | 6:31 | Play |

| The End Of A Love Affair | 3:11 | Play |

| East Of The Sun (West Of The Moon) | 5:15 | Play |

| Lover | 5:05 | Play |

| Yesterdays | 9:38 | Play |

| Bourbon Street Parade | 5:47 | Play |

Liner Notes

As Wynton Marsalis continues to make recordings, we are able to hear with ever greater definition how each one fits into his homemade and evolving artistic campaign. The tasks he has set for himself and how well he is measuring up to the broad territory of his ambitions become more audible. What Marsalis seeks is a place for himself within every aspect of the entire sweep of jazz, from New Orleans music to Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. Such a vision is unusual because it precludes obsession with a style, one particular way of playing that identifies the musician. Marsalis is interested in the entire music, from the place far below decks where the coal that fuels the engines is lifted shovel by shovel and thrown into the flame, all the way up to the most luxurious quarters, where even room service is luminous with grace.

Intimacy Calling is another involvement with the first-class accommodations of romance. It is put together with a direct clarity that shows the decision to come at these materials with the kind of confidence that allows for freedom from the circuitous. At this point, Marsalis has so many things at his command that he, like most major artists, is anxious to address the challenge of simplicity. Of course, there are ingenious rhythmic inventions we have learned to expect from his improvisations, and there is the domination of the instrument that allows for the projection of everything from the almost remotely subtle detail to the heroic gesture boomed out with the big feeling rooted in the field holler and the blues. Yet on this recording, Marsalis has chosen to approach these songs within lines of attack so superficially conventional that only the truly inventive could avoid the sinkholes of cliché’s and TV-dinner emotion.

“I love complexity,” Marsalis says, “but there is more to music than just that. When you listen to musicians like Louis Armstrong and Johnny Hodges, what you hear in their later work is that they aren’t involved with the kinds of wild things you hear them playing when they are kids. When they mature, they start honing in on the things that make their instruments different from other instruments. They address sound and what sound can do. Color becomes very important. It becomes as important as the notes themselves.

Then there is phrasing. They know how to sing up through the instrument. One of the things I’m working on now is the thing that you hear from those kinds of musicians. The music comes straight out with no pause. When you listen to Armstrong or Hodges you don’t think about anything except music – melody, chords, keys, rhythms, all of that disappears. It just appears as music. It’s like a batter when somebody is cooking something. Eggs, flower, milk, and all of that disappear; they become the batter. Even though each of them is important, each one’s identity disappears into that batter. That’s what I mean by people who make every element submit to the proposition of music.”

Marsalis is also talking about the difference between emotion and expression, which is considerable. Emotion is personal, but expression is objective, though even the most untalented are capable of emoting, only those who have been called by talented and chosen by their own will are in command of expression. Expression transcends the personal and allows us to recognize the objective – actually, communal-fact of heroic individuality. Heroic individuality achieves expression in the arts only when all of the elements are brought together for the overall effect of form, thought, feeling, technique, perspective, and spirit that we understand in terms of human consequence and give the names painting, dance, sculpture, theater, literature, cinema, and music. This sense of heroic individuality has taken on a distinctly democratic aspect over the last two centuries and is perhaps best expressed by Walt Whitman, who wrote, “I am multitudes.”

With Intimacy Calling, Marsalis brings his own heroic individuality to the expression of tenderness magnified and recalled by a stretch of trumpet tones and ensemble colors that are themselves contrasted by the celebratory swing of eroticism ascended to the diamond point of romantic precision. Songs are delivered with either consummate relaxation or form variations on the muscularity that results when the heart takes on the force of a bull turning its form against the magnetic rhythms of the object of ardor. it is in that range of passion that we hear how much Marsalis has developed since his first recorded ballad as a leader almost ten years ago, “Who Can I Turn To?”: We also hear the sort of development that can easily be attributed to an ease with his influences – Clifford Brown, Freddie Hubbard, Clark Terry, Miles Davis (before rock and roll), Don Cherry, Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro, Woody Shaw, and Louis Armstrong, whose importance and unchallenged supremacy the still-young Marsalis has come to understand most comprehensively over the last five or six years. The perspective Marsalis has on his influences and on what they represent in terms of the language of his instrument and of jazz itself gives his work heroic individuality, connecting it to the fact that no matter how original the masters might be, they are forever tipping their hats to the aesthetic parents their sensibilities demanded they choose.

Marsalis now has such freedom of choice that his playing constitutes the apotheosis of the trumpet in the music of this nation, its democratic reach is so inclusive that the multitudinous ruminations and suggestions of romantic experience, the recollections and the admonishments, the dreams and the residues of the blues are easily within his grasp. Marsalis has so worked on his sound that it can become as much of the statement as the notes and the rhythms he plays. Listen, as an example, to “Yesterdays” or to “You Don’t Know What Love Is.” he is also such a virtuoso that the whirlwind lyricism bebop brought to jazz is executed with Olympian ease on the astonishingly controlled and thematic “Lover” and “What Is This Thing Called Love?” There is the combination of both approaches heard in his rendition of “Embraceable You.”

The composing gift that has given us so many songs in so many moods over the last decade is represented here by “indelible And Nocturnal.” Those who recall “Think Of One,” which was the first enduring Marsalis arrangement, will appreciate how far he has come by the way he handles another Monk composition, this album’s “Crepsucule With Nellie.” Then there are also the tributes to Louis Armstrong and to New Orleans itself, “When It’s Sleepytime Down South,” and “Bourbon Street Parade.” There is also further proof of his contributions to the ranks of first-class young jazzmen, his discoveries and those he has provided with a perfect situation in which to develop – Bob Hurst, Jeff Watts, Marcus Roberts, Reginald Veal, Herlin Riley, Todd Williams, and Wes Anderson.

“I enjoy playing with all of these musicians and feel lucky to live in an era when things have progressively become clear about what the real deal is as far as serious study and serious honing of your craft is concerned. That is part of what I was after in picking the music we play on this recording. I wanted to interpret “Sleepytime” for two reasons: one is that it was Louis Armstrong’s theme song, and it also represents my attitude toward the South, which is, of course, something I share with Pops. Those who truly know the South know it for its warmth and its beauty, whether in the landscape or in the people. That’s a large part of the humanity you hear in Louis Armstrong; he was from the Crescent City. He was a Southerner. He was a fountain of warmth and humor and compassion.

” ‘You Don’t Know What Love Is’ ” has a perfect first line in the lyrics, and it’s a song that has the feeling of direct speaking. ‘Indelible And Nocturnal’ represented the challenge of writing a song to truly capture an experience. Because so many giants – Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, and Max Roach – have played ‘I’ll Remember April,’ I wanted to see what I could do with it. ‘Embraceable You’ is a melodic challenge and its lyrics combine with the music to make it what I combine with the music to make it what I consider one of the greatest songs in American popular music. There is also a flow to the harmonic progressions that makes it fun to play on.

” ‘Crepuscule With Nellie’ is one of those Monk masterpieces in which you can hear his gift for melody, harmony, and rhythm perfectly. It is also an example of how clearly he heard inside of the tradition, bringing a truly down-home quality that I have always loved to hear. It’s such an appropriately and perfectly realized use of a church feeling.

” ‘What Is This Thing Called Love?’ is another song that Clifford Brown and Max Roach recorded. I was trying to articulate something from a rhythmic standpoint on it. ‘The End Of A Love Affair’ comes from listening to Billie Holiday on ‘Lady in Satin,’ which is one of the all-time great recordings. I love her early work with Lester Young and all of those great musicians, too, but by this point in her career, Billie Holiday was on that level of nuance where everything must submit to music.

” ‘East Of The Sun (West Of The Moon)’ is a feature for Marcus Roberts, who is the most talented young pianist out here. When he was in my band, he was a nightly inspiration. This song got on the record because he and I first heard it on Louis Armstrong’s The Silver Collection, which we listened to day and night, one of the greatest documentations of late Armstrong and one of the greatest documentations of music-trumpet playing and singing.

“I put ‘Yesterdays’ on this recording because it has a lot of real long notes in the melody. It also gave me a chance to deal with some of the things that impressed me about Miles Davis when he was playing jazz. He really knew how to make a long note say something. I wanted to see how those long tones would work for me, If I could use them in my own style.

The last piece, ‘Bourbon Street Parade’ is here because it has a happy feeling and it reminds me of the fact that at the end of every dance we used to play – no matter what kind of a dance it was – we would play ‘The Second Line.’ I wanted to recapture that New Orleans feeling at the end of this recital. Maybe it will finish the record off for the listener with a little bit of the kind of joy I have often experienced in the Crescent City.”

Listeners to this recording will surely experience joy and will know again the sort of affirmation that is comprised of sensual dignity and dancing vitality, that forever opposes all reductions of intimate human activity to brute business, supplying the expressive liberation that vaults all truly amorous things over the tar pits of vulgarity. Yes, it is obvious that when Wynton Marsalis hears intimacy calling, he knows how to answer.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

1. WHEN IT’S SLEEPYTIME DOWN SOUTH

(O. Rene-L. Rene-C. Muse) Mills Music Inc./Otis Rene Pub./Leon Rene Pub.

2. YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT LOVE IS

(G. DePaul-D. Raye) MCA Music Pub. (a div. of MCA, Inc.)

3. INDELIBLE AND NOCTURNAL

(W. Marsalis) Skaynes Music

4. I’LL REMEMBER APRIL

(D. Raye-G. DePaul-P. Johnson) MCA Music Pub. (a div. of MCA, Inc. Pic Corp.)

5. EMBRACEABLE YOU

(G. Gershwin-I. Gershwin) W B Music Corp.

6. CREPUSCULE WITH NELLIE

(T. Monk) Thelonious Music Corp.

7. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE?

(C. Porter) W B Music Corp.

8. THE END OF A LOVE AFFAIR

(E.G. Reading) MCA Music Pub. (a div. of MCA, Inc.)

9. EAST OF THE SUN (WEST OF THE MOON)

(B. Bowman) Chappell & Co.

10. LOVER

(R. Rodgers-L. Hart) Famous Music Corp.

11. YESTERDAYS

(J. Kern-0. Harbach) Polygram Int’l Pub. Inc.

12. BOURBON STREET PARADE

(P. Barbarin) EMI Unart Catalog

Produced by Steve Epstein

Executive Producer: Dr. George Butler

Rhythm section on all songs except ‘What Is This Thing Called Love?” and ‘Bourbon Street Parade”:

Marcus Roberts, Piano

Reginald Veal, Bass

Herlin Riley, Drums

Rhythm section on “What Is This Thing Called Love?”:

Marcus Roberts, Piano

Robert Hurst, Bass

Jeff Watts, Drums

Rhythm section on “Bourbon Street Parade”:

Reginald Veal, Bass

Herlin Riley, Drums

Horn performances on “I’ll Remember April”:

Wynton Marsalls, Trumpet

Todd Williams, Tenor Saxophone

Horn performances on “Crepuscule With Nellie”:

Wynton Marsalis, Trumpet

Todd Williams, Tenor Saxophone

Wes Anderson, Alto Saxophone

Wynton Marsalis Mute Selection:

“Sleepytime Down South”, Bucket Mute

“Indelible And Nocturnal, Harmon Mute

“Lover”, Cup Mute

Wynton Marsalis does not perform on “East Of The Sun (West Of The Moon)”

Chief Recording Engineer: Tim Geelan

Assistant BMG Engineers: Dennis Ferrante, Sandy Palmer, James Nickols

Mixing Engineer: Tim Geelan

Recorded digitally at BMG StudJo A in New York City between September 1987 and August 1990.

Remixed at Sony Music postproduction facilities, New York City.

Mastered at Sony Music Studio Operations, New York City.

Special Thanks:

Marilyn Laverty, Kay Blackburn, Albert Ratcliffe, Kevin Gore, Don Ienner, Bob Willcox, The Flax Factor, Jo Didonato, Steve Epstein, Tim Geelan and Stanley Crouch

Exclusive Personal and Financial Management:

AMG International, PO. Box 55398, Washington, D.C. 20011,

Edward C. Arrendell II, Vernon H. Hammond III, Partners

Art Direction and Design: Josephine DiDonato

Photography: Ken Nahoum

Personnel

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Marcus Roberts – piano

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums

- Todd Williams – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

You Don’t Know What Love Is - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Al Ain, UAE

-

Videos

Videos

Embraceable You - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Warsaw (1994)

-

Videos

Videos

Bourbon Street Parade

-

Videos

Videos

Embraceable You - Wynton Marsalis Sextet at Newport Jazz Festival 1989

-

Videos

Videos

Yesterdays - Wynton Marsalis Quintet in New Zealand

-

Videos

Videos

Embraceable You - Wynton Marsalis Quintet in New Zealand

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis: Reclaiming the Jazz Tradition