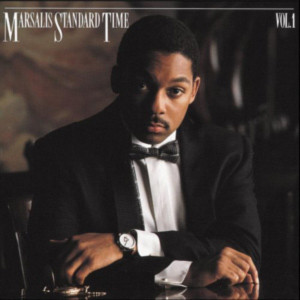

Marsalis Standard Time, Vol. 1

Wynton creatively explores ten standards, including “Caravan” and “Cherokee,” and two originals in a quartet setting featuring pianist Marcus Roberts, bassist Robert Hurst, and drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts. The result is a memorable encounter between jazz past and jazz present that gives more than a hint, surely, of jazz future.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quartet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | September 8th, 1987 |

| Recording Date | May 29-30, 1986 and September 24-25, 1986 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | 468713 2 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Caravan | 8:20 | Play |

| April in Paris | 5:04 | Play |

| Cherokee | 2:21 | Play |

| Goodbye | 8:19 | Play |

| New Orleans | 5:43 | Play |

| Soon All Will Know | 3:37 | Play |

| Foggy Day | 7:38 | Play |

| The Song Is You | 5:10 | Play |

| Memories of You | 4:06 | Play |

| In The Afterglow | 3:35 | Play |

| Autumn Leaves | 6:27 | Play |

| Cherokee | 2:28 | Play |

Liner Notes

Throughout this recording, the Wynton Marsalis Quartet delivers the sweep of the jazz sound with bold, unapologetic integrity. But by taking on selections from the standard repertoire that have inspired a good number of classic jazz performances, Marsalis and his men are placing themselves in a situation where their work has to be judged against the best of the entire tradition. Here they are challenged to assert their imaginations in contexts that are neither mysterious nor exotic, neither uncharted nor lacking in masterwork so imposing, more than a few musicians of this generation have chosen to avoid them altogether. But the Wynton Marsalis Quartet is not given to avoidance, which is why we observe fresh things happening to these familiar pieces, and spaces found for new footprints on ballroom floors scuffed and marked by hundreds of feet.

We hear these things because these young men share the awareness of a merciless fact that takes no prisoners into history: the responsibility passed on to the more ambitious artists of each generation is to learn how to redefine the fundamentals while maintaining the essences that give the art its scope and its grandeur. In jazz, those essences are swing, blues feeling, and the level of logical improvised response and development that gives ensemble playing the clarity of skillful orchestration. It is only by imaginatively addressing those essences that one can truly express his individuality and that an ensemble can actually evolve a characteristic imprint on the specific riches of the aesthetic.

The quality of imagination, skill, and spirit that brings such freshness to the arrangements and the improvising on this record should be obvious. But it might not be o obvious that what we hear is the result of a willingness to sweat in the woodshed, to regain levels of ability that have declined in jazz just as they have in American education. As Christopher Lasch points out in The Culture of Narcissism, “People increasingly find themselves unable to use language with ease and precision, to recall the basic facts of their country’s history, to make logical deductions, to understand any but the most rudimentary texts, or even to grasp their constitutional rights. The conversion of popular traditions of self-reliance into esoteric knowledge administered by experts encourages a belief that ordinary competence in almost any field, even the art of self-government, lies beyond the reach of the layman.”

If we substitute jazzman for layman, and the fundamentals of improvising for language skills, the recalling of basic facts, logical deductions, the understanding of rudimentary texts, and if we realize how popular trends of the last twenty years have led to what were once elemental abilities being considered the resources of those now defined as elitists, we can better appreciate the task Wynton Marsalis and his musicians have set before themselves. In order to address how much sophisticated learning has been lost or largely forgotten — when not arrogantly dismissed — these young men have had to go backward in order to move forward. In pursuit of a more inclusive body of information, skill, and feeling, they have had to separate themselves from those trend-victims and theorists who use every possible argument to sidestep the weights and achievements of history.

“When I was growing up,” says Marsalis, “the rendering of one bebop lick made you a jazz expert. Though my father constantly tried to pull my coat, I still thought I could play. I was greatly mistaken. In my generation, we didn’t know how to play the blues, couldn’t improvise over chord changes, didn’t know anything about swinging — and didn’t care either. We interpreted all of those musical skills as expressive of a bygone era that had no relevance to us. A serious misconception. But when I was fortunate enough to get constructive criticism from musicians like Art Blakey and Ron Carter, I began to discover all the things that were missing from my playing that my daddy tried to tell me about before. I took it upon myself to learn what I had missed. In doing so, I have come to learn in progressively greater detail how much has been conceived and executed with the highest degree of artistic quality and feeling. So what I’m working on is everything I can that musicians like Louis Armstrong, Bird, Monk, and Coltrane thoroughly mastered — blues, swing, and popular songs.”

His studies have inspired a conception of group improvising that submits to the revelations of swing but also extends ensemble polyrhythm into the arena of metric counterpoint. In this music, the steady beat that has been so essential to swing is spontaneously replaced by the demarcations of the form. In a thirty-two bar AABA tune in four/four, each of the eight bar sections becomes the time, which is heard as thirty-two quarter notes, not a specific meter. Phrases replace meters and are extensions of things heard on J Mood, where this conception had reached a high degree of authority, which must now be understood as a predictive preamble to what these musicians are capable of at this point. They are on the verge of a subtle but persuasive expansion of jazz time that should have great influence over the next few years.

“Every instrument,” says Marsalis, “is allowed the freedom to interpret the form from a different metric vantage point. This frees Marcus, Bob, and Jeff from having to keep a strict basic time, but gives them the responsibility of resolving superimposed meters correctly in the original form. Though we are approaching the form with rhythmic and metric freedom, everyone has to work within the flow of the improvisation. The last thing I’m interested in is freedom that can only justify itself by its existence. I’m interested in freedom that encompasses the fundamentals of music, allowing for inspiration rather than desperation.”

None of those ideas would amount to more than high-level journeyman work were they not backed up by the component of human feeling that makes aesthetic expression whole. That wholeness is more audible than ever as Marsalis continues his disciplined development. What we hear is deepening emotional substance in the long, long phrases, the metric modulations, the complex harmonies, and the synthesis of the tender and the tempestuous expected of the ballad well sung. His sensitivity to tonal color and to rhythm has resulted in the trumpeter making exceptional use of his mutes and his sound. The effect of that sound is very different when the clarion surge of the winging “Caravan” improvisation is compared to the awesome purity that radiates through “Goodbye.”

In the first piece, there is exceptional thematic control and a second bridge that is one of the most seamless trumpet inventions of the last few years. The four-note motif that Marsalis superbly develops throughout “Goodbye” for an effect of pathos and loss illustrates his ability to maintain structure while delivering lyric content. Then there is “April In Paris,” another thematic marvel in which the arrangement itself inspires arresting rhythms; the prickly tenderness of “In the Afterglow,” an original that gives the trumpeter an opportunity to speak of soft, three-dimensional recollections; the assured melodic motion through the mobile of rhythms and meters on “Foggy Day”; the unexpected delicacy that alternates with broiling passion on “Cherokee”; the arrogant plasticity of swing heard in “The Song Is You”; his almost raucous salutes to Harry Edison on “Soon All Will Know,” and so on.

But there is one element that holds all of those Marsalis improvisations together and that separates him from nearly all of the old and the young: rhythm. At this point, Marsalis probably plays the most rhythmically complex phrases of any trumpeter other than Dizzy Gillespie. His studies of Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Gillespie, and Don Cherry have given birth to a way of dicing the beat for subtle to startling accents that suggest a new frontier of phrasing. Though there is clearly a percussive lilt to his time, Marsalis takes advantage of his playing a wind instrument to sustain notes in unexpected places so that the long, long lines are rarely delivered in streams of eighth or sixteenth notes. As his playing on “New Orleans,” “April in Paris,” “Caravan,” “Cherokee,” “Foggy Day,” and “The Song Is You” shows, Marsalis is already doing extremely fresh things with time. Quite clearly, we hear a technical strength balanced by an expressiveness and a swing that make it clear Wynton Marsalis will continue to take more names as time passes.

The wonder of this recording, however, is that we hear such informed boldness from the leader and his players. Only extremely sophisticated musicians could make such complex arrangements swing so authoritatively (e.g., “The Song Is You”), then play with the time so effectively, creating and resolving tensions with an often stunning capacity for grace. The protean accuracy of the adjustments to one another and to the forms of the tunes makes it rather obvious that this is one of the best jazz groups now working. Yes, Marsalis has found himself some extremely talented players.

Marcus Roberts is, doubtless, the most soulful pianist of his generation. He sounds as though he has somehow been born knowing that the spiritual function of the blues feeling is to make clear the distinction between tragic recognition and self-pity. Roberts has also made a miraculous synthesis of the principles that were idiomatically enunciated with such consistent lyricism, swing, and integrity by Ellington, Basie, and Monk. Consequently, Roberts knows how to make the piano creep a meaning up on you, or flutter some fancy-footed melodic flourishes, or pull buried treasures out of well-hidden places in the beat, or pitch harmonic curve balls that just cross the corner of the plate, striking out even the very slightest inclinations towards sentimentality.

As a section player, he tends to create piano parts instead of merely stating chords, parts that work as dialogue or counterpoint, as agent of rhythmic contrast or timbral variations — and always as harmonic percussion or multi-noted emulations of Negro vocal effects. In his features, Roberts is ever aware of the theme and never fails to make the most of the material played by the previous improviser. On “Autumn Leaves,” he takes the last notes from Marsalis and builds a statement that moves further and further away from the basic beat. On “April In Paris,” Roberts uses the material the trumpeter improvised in his last eight bars for the bridge and last eight of his own first chorus. He then reintroduces us to the old jazz feeling of tipping, lowering the dynamics and softly massaging the beat for a bittersweet statement. His second chorus maintains thematic attention, the bridge returning to the ideas used in the middle eight of the first chorus. The way Roberts uses his left hand as much for sparse counter-melodies as he does for harmonies on the solo feature, “Memories of You,” proves without a doubt that he is a man who never sleeps through the soul call.

From his first notes on “Caravan,” it is obvious that Bob Hurst has a thorough understanding of the percussive qualities demanded of the bassist who will meet the ultimate jazz criteria — swinging with melodic and harmonic resources that affirm both the joys of the sensual throb and the complexities of consciousness beyond the boodie. His pitch is superb and he has extended the gifts already noticeable on J Mood. Hurst has undoubtedly listened to those who didn’t drain the grease off the beat by falling for cello imitations. In his subtle handling of his place in the time and his willingness to seek the perfect idea that enhances the sound of the band instead of drawing attention to himself, Hurst sometimes pivots the whole ensemble on his four strings. Listen to what he does on the bridge of the first improvised chorus of “Cherokee,” where he breaks the bass line into percussive patterns that add complexity to the time but don’t drop the swing. Then there is his groove on the blues, “Soon All Will Know,” where he plays as though each string was intended to put a tip on the tingle of swing. There are no young bassists more impressive, and few even close to the quality of imaginative spark and wit Hurst brings to his work.

Jeff Watts remains at the forefront of younger drummers by virtue of his swing, his musical sensitivity, his invention, and the refined conception of timbre he uses for brilliant additions of color. Watts is also an interesting thinker whose arrangement of “Autumn Leaves” changes meters every bar up to the release by adding a beat (1, 12, 123, 1234, 12345, 123456, 1234567, 12345678). He can play boodeen-pelvic grooves like the one on “Caravan,” execute alternate cross-rhythms with the piano while keeping the time and swinging up next to the trumpet on “The Song Is You,” and shape distinctive thrusts for the pulses of the songs. But all of it is made valuable by the width of swing he brings to each piece, working with different parts of the bar, using his cymbals for emotive shouts or as metal resonators of crystalline lyricism, and stocking rhythms in percussive parts that give multiple tensions to the time. In fact, the singing qualities of percussion hear from him on “Goodbye,” “Foggy Day,” and “New Orleans” seem an Afro-American version of the techniques used in the “talking” drumming of West Africa. Where the Africans bend vocal pitches through the heads of their drums. Watts builds upon the ringing expressiveness of the cymbals that is so essential to the feeling of jazz. He deftly produces the slurs, moans, whispers, calls, shouts, and delicate cries central to the melancholy, the celebration, and the projection of the itch to twitch at the soul center of the blues passion.

From the opening gumbo street beat that redefines the dance pulsation of “Caravan,” through the audacious multiple angles on the express tempo of the concluding version of “Cherokee,” these young men prove that the bloom of the unique can often be most easily recognized within the context of the familiar. Yes, Wynton Marsalis, Marcus Roberts, Bob Hurst, and Jeff Watts show us that there is a seriousness, adventure, wit, and idiomatic skill in the air, and that that very air threatens to become a storm of increasingly glorious invention. As you listen to these performances, some of that glory will surely reveal itself. “Soon All Will Know.”

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

Musicians:

Wynton Marsalis, Trumpet

Marcus Roberts (“J Master”), Piano

Robert Leslie Hurst III, Bass

Jeff “Tain” Watts, Drums

Executive Producer: George Butler

Producer: Steve Epstein

Chief Engineer: Tim Geelan

Assistant Engineer: Dennis Ferrante

Recorded, digitally at RCA Studio A on May 29-30, 1986 and September 24-25, 1986

Recorded on to the Sony PCM 3324 digital 24 track tape recorder through an MCI console.

LP mastered by Europadisk

“Autumn Leaves” Arranged by Jeff “Tain” Watts

“Memories Of You” Marcus Roberts (“J Master”), Solo Piano

All other original arrangements by Wynton Marsalis

Art direction: Josephine DiDonato

Photography: Ken Nahoum

Special thanks: Steven Epstein, Tim Geelan, Delfeayo Marsalis, “E” and Stanley Crouch.

Exclusive management by AMG International

Edward Arrendell, II

Vernon H. Hammond, III – Partners

P.O. Box 55398

Washington D.C. 20011

Personnel

- Marcus Roberts – piano

- Bob Hurst – bass

- Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Goodbye - Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Dizzy’s Club 2014

-

Videos

Videos

Cherokee - Wynton Marsalis Sextet at Newport Jazz Festival 1989

-

Videos

Videos

Cherokee - Wynton Marsalis Quintet in New Zealand

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton Marsalis Quartet at North Sea Jazz Festival 1987

-

Wynton's Blog

Wynton's Blog

Ellis Marsalis playing “In The Afterglow”

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis: Reclaiming the Jazz Tradition

-

News

News

Trumpeter Marsails personifies jazz