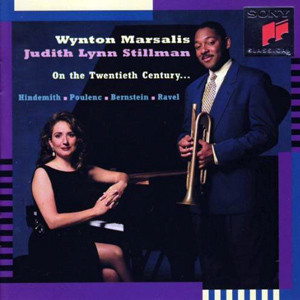

On the Twentieth Century

A bracing tour of 20th century compositional styles, the program includes Maurice Ravel’s “Habanera,” Arthur Honegger’s “Intrada for trumpet and piano,” Halsey Stevens’ “Sonata for trumpet and piano,” Francis Poulenc’s “Eiffel Tower Polka,” Leonard Bernstein’s “Rondo for Lifey,” and Paul Hindemith’s “Sonata for trumpet and piano.”

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis with Judith Lynn Stillman |

|---|---|

| Release Date | September 21st, 1993 |

| Recording Date | January 21-24, 1992 |

| Record Label | Sony Classical |

| Catalogue Number | SK 47193 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Classical Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Piece en forme de Habanera – (Maurice Ravel) | 3:16 | Play |

| Intrada – (Arthur Honegger) | 4:14 | Play |

| Triptyque – (Henri Tomasi) | ||

| I. Scherzo | 0:48 | Play |

| II. Largo | 1:14 | Play |

| III. Saltarelle | 1:42 | Play |

| Sonata for Trumpet and Piano – (Halsey Stevens) | ||

| I. Allegro moderato | 5:41 | Play |

| II. Adagio tenero | 5:25 | Play |

| III. Allegro | 3:28 | Play |

| Eiffel Tower Polka – (Francis Poulenc) | 0:51 | Play |

| Legende – (Georges Enesco) | 6:26 | Play |

| Rondo for Lifey – (Leonard Bernstein) | 1:29 | Play |

| Rustiques – (Eugène Bozza) | 7:23 | Play |

| Sonate fur Trompete und Klavier – (Paul Hindemith) | ||

| I. Mit Kraft | 4:57 | Play |

| II. Massug bewegt – lebhaft | 2:20 | Play |

| III. Trauermusik | 8:38 | Play |

Liner Notes

This recording invites you to listen to a broad swatch of twentieth-century European and American trumpet repertory, performed by one of the finest trumpet players of all time. None of the pieces, frankly, can be considered among the great memorable masterpieces – the pantheon – of the classical literature. But Wynton Marsalis imbues them all with his special brand of cool authority and refined sensitivity, making them sound fresh and inviting.

In some ways Hindemith’s Sonata for Trumpet and Piano is the most important and substantial work in this collection. In 1939 Hindemith, newly arrived in America, a refugee from Hitler’s Nazi Germany where his music (although Hindemith was not Jewish) had been banned since 1934, continued his work on two major cycles: a series of concerti for various instruments and a parallel series of sonatas for solo instruments and piano. This cycle was eventually to extend over fifteen years and comprise more than a dozen sonatas (plus a sonata for solo harp and one for four horns). Remarkably, this extraordinary burst of creativity benefited all manner of instruments, including many of the neglected ‘underdog’ instruments of the orchestra (double bass, bassoon, tuba, trombone, English horn, alto horn), for whom there was at the time virtually no solo repertory.

Although we are now, some fifty years later, much more aware of a vast literature for trumpet from the Baroque era and can thus hardly consider the trumpet a ‘neglected underdog,’ in 1939 Hindemith’s sonata appeared as a major enrichment of and much welcomed addition to the then still rather slim trumpet repertory.

Arguably, the Trumpet Sonata is one of the finest – if not the finest – of the entire series, although one can imagine that tuba and horn players, trombonists and bassists might take prideful umbrage at that thought. Cast in three movements (I. With Strength; II. Moderately moving; III. Funeral music, very slow), the sonata skillfully blends traditional elements with modern mid-twentieth-century concepts. For example, the three movements are firmly anchored in B-flat – F – B-flat major respectively – ideal keys for the trumpet – but within movements the musical occasionally wanders far astray into atonal chromaticism. This in turn is modified by Hindemith’s penchant for emphasizing the ‘pure intervals’ of fourths and fifths, a kind of leavening in the spicy seasonings of chromatic atonality.

It is this remarkable balancing act between the old and the new as well as his almost legendary ability to write idiomatically for any given instruments that has made Hindemith’s music so accessible to audiences, admired by conductors and instrumentalists, and especially beloved by woodwind and brass players. He is their friend, for he wrote music specifically for them to play when hardly anyone else did. And he wrote well for them: music that sounds well and is not too difficult or impossible to play. It is not for naught that the term Gebrauschsmusik – practical, functional music – has been admiringly bestowed on Hindemith’s oeuvre. The Trumpet Sonata is a shining example of Hindemith’s craft and love of instruments at its best.

Like Hindemith, Halsey Stevens (1908-1989) wrote an enormous amount of chamber music for all manner and combinations of instruments. Indeed, he too has composed a substantial series of sonatas that, in intent, choice of instruments, and time of creation very much parallels Hindemith’s cycle – a fact that has led some wags to call Stevens “the American Hindemith.” To infer from this that Stevens is a mere Hindemith epigone would be quite unfair, for his idiom and style are very much his own. If there is here and there a mild affinity for Hindemith’s style, it is interbred with a much closer linguistic identity to the music of Copland and Bartok. (Steven’s 1953 The Life and Music of Bela Bartok was one of the earliest studies of that composer and has long been considered a standard work on the master.)

Steven’s Trumpet Sonata was written in 1956 and in its three movements (fast-slow-fast) epitomizes Steven’s mature style: a successful blend of well-profiled, no-nonsense thematic material, a healthy rhythmic drive and clarity of form. As in the Hindemith work, the trumpet writing is both virtuosic and felicitously idiomatic. No wonder it has become one of the most trumpet players’ favorite solo pieces.

The great Romanian violinist and composer Georges Enesco (1881-1955) is best known for his two Romanian Rhapsodies and – more recently – for the revival of his magnum opus, the opera Œdipe. His Legend for trumpet and piano is a brief single-movement rhapsodic work, reflecting his close contact with French music musical life and composer (Debussy, Ravel, his teachers Massenet and Fauré) during the nearly forty years Enesco lived and worked in Paris. Though beautifully written for the trumpet, there is no denying that the solo part is also informed by a certain lyricism and singing quality very much associated with the violin, Enesco’s favorite instrument. This quality serves Wynton well, for if anyone knows how to sing on the trumpet these days it is Wynton Marsalis.

Maurice Ravel’s Habanera, written as a solo piano piece when the composer was only twenty, not only garnered him his first major public success (in 1898), but remained so dear to his heart that he sanctioned arrangements for any number of instruments (flute, violin, trumpet, cello, etc.) and in 1907 incorporated it, somewhat reworked, in his evocative Hispanic orchestral masterpiece Rapsodie espagnole. With its undulating rhythms and languorous ‘hot weather’ melodies – its tempo marking, “rather slow and with indolence,” tells it all – the work is a superb vehicle for Wynton’s lyric style and easy sense of swing.

Henri Tomasi (1901-1971) is best known in America for his Trumpet Concerto (an outstanding work which Wynton recorded for Columbia almost a decade ago), while in his native France he was most admired for his many stage works and ballets. And like Hindemith and Stevens, he has composed a great number of concertos – sixteen in all – for all sorts of instruments. Triptyque, written in the mid-1950s, is a very brief (as its title implies) three-movement work: Scherzo-Largo-Saltarelle. The last-named is a particularly fetching virtuoso piece for muted trumpet, based loosely on the old Spanish and Italian saltarello, a very fast jumping dance in triple meter. Wynton’s flawless execution here is something to behold.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of solo and recital pieces have been written over the years for all conceivable instruments as contest pieces in connection with two major and venerable institutions: the Geneva International Competition and the Paris Conservatory. For the former, the great Swiss-French composer, Arthur Honegger wrote his Intrada in 1947; for the latter Eugène Bozza wrote his Rustiques, one of his many solo pieces for trumpet, in 1956.

Honneger is, of course, best known for his five splendid symphonies and major choral/oratorio works like Jeanne d’Arc and Roi David. Enormously prolific, he also wrote nearly forty film scores and mountains of chamber music. His Intrada, a modest piece cast in a simple ABA form (Maestoso-Allegro-Maestoso), reflects well his personal musical language: a free, easy mixture of the tonal, polytonal and atonal.

Bozza (b. 1905) has been for many decades not only one of France’s most prolific composers but, like Hindemith and Stevens, a great boon to woodwind and brass players. His hundreds of solo and recital works have involved virtually every known instrument and instrumental combination, from consort pieces for three bassoons, six clarinets, four flutes, four horns, and innumerable woodwind and brass quintets to solo works for everything from the piccolo to the contrabass. This vast repertory – the lovely Rustiques included – shows with a remarkable consistency Bozza’s gift for melodic fluency, elegant forms and a keen sense of how to make an instrument – any instrument – sound good and right.

The program is rounded out by two entertaining trifles, one by Francis Poulenic, the other by Leonard Bernstein. The Poulenc item, incidentally for two trumpets, both played by Wynton through the magic of overdubbing, is one of the two brief, purposely silly numbers Poulenc contributed to a collective work composed by five members of “Les Six” for a play by Jean Cocteau in 1921, the heyday of surrealism and dadaism.

Finally, there is Bernstein’s lighthearted Rondo for Lifey, part waltz, part fox-trot, paying tribute to a skye terrier, named Lifey, owned by Lenny’s actress friend Judy Holliday.

What ties all this diverse music together into a cohesive, entertaining program? Well, there are those certain obvious similarities in the pieces: all those little related B-flat fanfares (Hindemith, Stevens, Bozza), the flashy chromatic runs in the cadenzas (Bozza, Enesco, Ravel), the difficult sounding but easy-to-play triple-tongue passages (Bozza, Enesco, Stevens), the imperiously noble themes (Hindemith, Enesco, Honegger), the tarantella-saltarello dancing musics (Bozza, Tomasi) – all eminently trumpetistic ideas and gestures.

But beyond all that there is the shining beauty of Wynton’s tone and clarity of conception. Those are very rare gifts which Wynton and his able partner Judith Lynn Stillman hereby extend to you. Enjoy!

–Gunther Schuller

Credits

MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937)

1. Pièce en forme de Habanera

Transcribed for Trumpet and Piano

ARTHUR HONEGGER (1892-1955)

2. Intrada

HENRI TOMASI (1901-1971)

Triptyque

3. I. Scherzo

4. II. Largo

5. III. Saltarelle

HALSEY STEVENS (1908-1989)

Sonata for Trumpet and Piano

6. I. Allegro moderato _LI II. Adagio tenero

7. III. Allegro

FRANCIS POULENC (1899-1963)

8. Eiffel Tower Polka

(Les Mariés de la Tour Eiffel: “Discours du général”)

(Transcribed by Don Stewart)

Wynton Marsalis, Trumpet l & 2 (Synchronization)

GEORGES ENESCO (1881-1955)

10. Legende

LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918-1990)

11. Rondo for Lifey

EUGENE BOZZA (‘1905)

12. Rustiques

PAUL HINDEMITH (1895-1963)

Sonate far Trompete und Klavier

13. I. MitKraft

14. II. Mässig bewegt – Lebhaft

15. III. Trauermusik. Sehr langsam; Ruhig bewegt–Alle Menschen müssen sterben. Sehr ruhig

Wynton Marsalis, Trumpet

Judith Lynn Stillman, Piano

Total time: 56’29

For this recording 20-bit technology was used for “high definition sound”.

Producer: Steven Epstein

Engineer: Charles Harbutt

Editing Engineer: Robert R Wolff

Mixing Engineer: Ellen Fitton

Technical Supervisor: Billy Rothschild

Recorded in Richardson Auditorium at Alexander Hall, Princeton University, New Jersey, January 21-24, 1992

Personnel

- Judith Lynn Stillman – piano