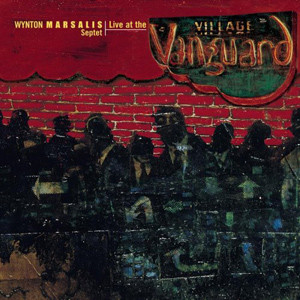

Live at the Village Vanguard

The Wynton Marsalis Septet’s sold out stands at the Village Vanguard have become an annual event on the jazz calendar. Wynton calls the nights on which this seven CD set was recorded “the best time I ever had in my life.” For those of us not lucky enough to have been in the audience, here’s a chance to sit in on an entire week’s worth of sets, as seven extraordinary musicians play jazz music in a spirit that all who were there surely remember as, in Wynton’s words, “pure, full of love, and plenty of fun.”

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Septet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | December 6th, 1999 |

| Recording Date | 1990, 1991, 1993, 1994 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | CXK 69876 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| DISC 1 – Monday Night | ||

| Welcome #1 – (Live) | 0:42 | Play |

| Cherokee – (Live) | 6:53 | Play |

| The Egyptian Blues – (Live) | 8:10 | Play |

| Embraceable You – (Live) | 5:27 | Play |

| Black Codes From the Underground – (Live) | 16:32 | Play |

| Harriet Tubman – (Live) | 13:42 | Play |

| Monk’s Mood – (Live) | 3:01 | Play |

| And The Band Played On – (Live) | 5:34 | Play |

| The Cat In The Hat Is Back – (Live) | 9:28 | Play |

| (Set Break) – (Live) | 6:44 | Play |

| DISC 2 – Tuesday Night | ||

| Welcome #2 – (Live) | 1:23 | Play |

| Uptown Ruler – (Live) | 14:12 | Play |

| Down Home With Homey – (Live) | 18:04 | Play |

| Reflections – (Live) | 6:07 | Play |

| Jig’s Jig – (Live) | 12:12 | Play |

| Sometimes It Goes Like That – (Live) | 6:49 | Play |

| In A Sentimental Mood – (Live) | 3:47 | Play |

| Knozz-Moe-King – (Live) | 8:22 | Play |

| (Set Break) – (Live) | 5:31 | Play |

| DISC 3 – Wednesday Night | ||

| Welcome # 3 – (Live) | 0:37 | Play |

| Buggy Ride – (Live) | 8:55 | Play |

| I’ll Remember April – (Live) | 8:04 | Play |

| Stardust – (Live) | 5:19 | Play |

| In The Court of King Oliver – (Live) | 7:50 | Play |

| Bona & Paul – (Live) | 2:08 | Play |

| Four In One – (Live) | 11:55 | Play |

| Way Back Blues – (Live) | 6:44 | Play |

| Rubber Bottom – (Live) | 6:10 | Play |

| Where’s The Music – (Live) | 3:43 | Play |

| Play The Blues And Go – (Live) | 8:56 | Play |

| (Set Break) – (Live) | 5:04 | Play |

| DISC 4 – Thursday Night | ||

| Welcome #4 – (Live) | 2:00 | Play |

| Pedro’s Getaway – (Live) | 16:29 | Play |

| Evidence – (Live) | 4:28 | Play |

| Embraceable You – (Live) | 12:07 | Play |

| A Long Way – (Live) | 12:42 | Play |

| The Arrival – (Live) | 12:57 | Play |

| Misterioso – (Live) | 6:01 | Play |

| Happy Birthday – (Live) | 1:02 | Play |

| The Seductress – (Live) | 4:36 | Play |

| (Set Break) – (Live) | 3:54 | Play |

| DISC 5 – Friday Night | ||

| Welcome – (Live) | 0:33 | Play |

| The Majesty of The Blues – (Live) | 15:45 | Play |

| Flee as a Bird To The Mountain – (Live) | 3:12 | Play |

| Happy Feet Blues – (Live) | 6:26 | Play |

| Thelonious – (Live) | 4:46 | Play |

| Stardust – (Live) | 6:45 | Play |

| Intro to Buddy Bolden – (Live) | 2:10 | Play |

| Buddy Bolden – (Live) | 5:46 | Play |

| Swing Down Swing Town – (Live) | 9:36 | Play |

| Bright Mississippi – (Live) | 8:38 | Play |

| (Set Break) – (Live) | 3:04 | Play |

| DISC 6 – Saturday Night | ||

| Welcome #6 – (Live) | 0:59 | Play |

| Citi Movement – (Live) | 40:24 | Play |

| Winter Wonderland – (Live) | 9:03 | Play |

| Brother Veal – (Live) | 4:30 | Play |

| Cherokee – (Live) | 11:52 | Play |

| Juba and A O’Brown Squaw – (Live) | 4:48 | Play |

| DISC 7 – Sunday Night | ||

| Welcome #7 – (Live) | 0:36 | Play |

| In The Sweet Embrace of Life – (Live) | 54:43 | Play |

| Local Announcements – (Live) | 4:45 | Play |

| Altar Call – (Live) | 10:42 | Play |

| Final Statement – (Live) | 6:00 | Play |

Liner Notes

Bandstands in jazz clubs are altars of swing and there is no more famous altar than the one in the Village Vanguard, which is the oldest jazz club in the world and the one in which the most swing has been dispensed. The Vanguard is a basement which one enters by walking down the stairs. It is on Seventh Avenue in Greenwich Village, which means that there is always something going on outside the club. There might be a tourist bus full of Japanese loaded down with cameras and stepping onto the sidewalk as though they are now in the presence of a very special American temple, which they are. Any imaginable kind of person, dressed any kind of way, might be ambling north or south on Seventh Avenue and stop in front of the club to say that he or she remembered when some you-know-who was playing down there, back in the day. Somebody this same person knew who’s now dead worked there and got him or her in, either through the front door or the back door. A listener old as the hills could recall when Harry Lim, the Japanese lover of swing music, used to organize jam sessions at the Vanguard in the forties, which established masters and a genius named Dizzy Gillespie attended, instruments at the ready. Another who worked in radio and now lives in Japan could tell you of how he came upon John Coltrane and Red Gardland having a conversation near the stairs at the back of the club about the sexual rites of wolves, with Coltrane speculating hilariously on the erotic psychology of the male wolf. Or who could forget, as Elvin Jones once said, how Thelonious Monk had such a large presence that he could sit near the end of the bar late at night when the club was nearly empty and fill up the entire space? Or the apocryphal night that Max Roach and Charles Mingus, bent on rattling Ornette Coleman (who was playing his saxophone with only bass and drums), devised a plan at a bar across the street. Roach loudly came in pretending to have lost his mind and began banging on the piano and asking wy it wasn’t being used, then Mingus, dressed in black from head to toe, came down the stairs, picked Roach up and put him across his shoulder, turned to look at the audience, and left. Those are some of the things that make the club what it is and place it within the realm of myth, where Americans of all colors and people from many countries have gathered either to play or to listen or to do both and hang out laughing and reminiscing about the bad times and the good times.

On an unsuspecting night, a customer might be accosted by an atrocious and rightfully unemployed drummer who promotes himself endlessly, trying to force a tape of his one recording on whomever lacks the intuitive smarts to give him no more than a nod and a brush off. For a few years he was banished from standing in front of the club because he began-out of nowhere–collecting admissions as people waited to get in and made off with the bucks. At present, like so much of what makes New York exactly the thing that it is, he is back now and again.

On a good night, lined up outside with others ready to get a healthy dose of Americana in rhythm and tune, one feels the emotion of being among very special people. These are jazz people, no matter where on this earth they might come from. These are people who listen beyond the commercial arenas and beyond the drum machines and the overlaid patching together of bits that have transformed the making of pop recordings into something much more like movies than the art of jazz, in which the refined skills of interacting musicians construct the art on the moment. But those people in that Vanguard line with you out there, the ones who will come if it’s hot or cold or raining or snowing, they are people who want to hear some musicians get up on that bandstand and perform. They want to witness that interplay in which the present is taken over and the glow of life given form seeps into or sears its way through the air. Such people, down in the deeper parts of their souls, seek the experience of becoming better versions of themselves.

Jazz people know swing is what they’re after. Why? Because swing, as one musician observed, is the sound of support and welcome and recognition. So those listeners want to be in on that number, that improvised occasion when the entire room–everything on the bandstand and off the bandstand–becomes one force defined by swing. I’m talking about when swing becomes both invisible and solid. Then all that falls within hearing distance starts swinging and becomes that swing. That, for those of you who don’t know, is the highest aspect of the performance relationship between the jazz musician and the jazz listener and the jazz place. In that relationship, the willing listener hears something both extremely sophisticated and, at its best, no more than a note away from an equally greasy condition. That combination of high-minded expression and the gutbucket funk of the blues–the sweet stink of love and the filthy of the rot ever encroaching on existence–is what makes a jazz moment particular in its feeling. The feeling of jazz, finally, is something adult, not adolescent. Listeners either aspire to that grand condition of the grown-up or, as with those who are there already, they wish no more than reaffirmation swung so hard or crooned in jazz time with so much charisma that the wounds, the toil, and the heartbreak become no more than spiritual seasoning. That’s why jazz people have a different look to them, no matter their point of origin; they are seekers and veterans of sophisticated feeling.

The Village Vanguard, so steeped in those moments and those far, far more than a thousand nights of magical tale-telling, is the perfect place to get the full weight of jazz laid on you. One of the reasons is that the sound up on that bandstand and out in that room has no equals, just as the club has no dressing room, only a kitchen where musicians and their friends hang out and talk before or between or after shows. there used to be food served but that’s over. Now all you can get is a drink and a place to sit. Some of the people who used to work the door but are now gone gave the place a reputation for demanding money for abuse. Audiences endured them because of where they were and who was playing there.

The late Max Gordon (1903-1989) started the whole thing in the middle thirties and was there almost every night, even when he was in his eighties and tumbled down the entire length of the stairs, only to sit at a table near the door until closing, his overcoat still on, his face not exactly dazed but at a distance in its demeanor from everyone and everything in the room. A tough old bird as they used to say. He was some character, that Gordon, short, full of brine and vinegar, an Eastern European Jew who grew up in Oregon, had a prominent forehead and smoked bad cigars because, as he said, “I’m a cheap sonofabitch.”

Gordon sometimes was seated in the very back of the club under a WPA painting of a nude, where he drank champagne with a pretty girl on either side of him, patting them occasionally and referring to each of the fillies as dollink. Sometimes he sat in the kitchen at his desk across from the stove that was no longer used for anything and told stories of the Depression or of how one famous singer who hustled hot furs in his club during an engagement removed an entire full-length mink from a very small bag and handed it to her driver, who made the sale. He could tell you about Miles Davis, the haughty emperor of resentment, and all of his girls, famous and not famous, some so beautiful one’s eyes had to be overhauled after looking at them. There was John Coltrane, a quiet man whose enormous, sustained intensity eventually gave way to endless hysteria on the bandstand and sovereign gloom during the breaks. Blowing some of his last songs, Coleman Hawkins, in full gray beard as death leaned on him, filled his tenor saxophone and the room and would, every so often, stop after he played a phrase he liked and laugh as though he were at home alone, not working in front of an audience. Thelonius Monk, always tardy and sometimes coming down the steps in heavy collisions of shoe leather and concrete, not even removing his coat and going straight to the piano, once explained to Gordon that he was late for work because the downtown subway train he got on started going backwards! Old man Gordon and the entire Count Basie band in the Vanguard for one night. There was the time that Louis Armstrong came in and every light became brighter, even the glint on the instruments took on more power, and that man, the king of jazz, talked to everyone as though he had known them since the day he was born, now and again telling remarkably bawdy stories. Duke Ellington, the grandest expression of ongoing genius in jazz, sat in a corner and listened intently then gave the waitress a fat tip before floating up the stairs like a very expensive cologne so out of the ordinary that it had never had a name. The little club owner brought them in all in there at one time or another, if they were great or not so great, if they performed or if they only listened, or didn’t seem to listen as they joked around in the kitchen or in the hallway behind the bar and near the bathroom while somebody else was up on the bandstand playing as if heaven and earth depended on every note. So when you saw Max Gordon, he carried the spirit of jazz inside him as a facilitator, a patron, and a witness, just as he shuffled along in his running shoes one night, carrying a pile of bucks in both hands to his desk, growling, “Ah, money. I hate this shit.”

The trumpeter’s manager, Ed Arrendell, part of the young, feisty, and adventurous crew that distinguished the bandleader’s artistic, social, and business situation, made the first deal with Gordon in 1983. Then, Wynton Marsalis began bringing his septet into the Village Vanguard, after first moseying down the stairs during the earlier eighties and sitting in with trumpeters like Clark Terry, Woody Shaw, and Jon Faddis. In that more than special room, the young man, his band, and their music were swirled round by the spirits of a place where legend was made and sustained. He was himself something of a legend at even so early an age because Marsalis had very quickly become a force much more formidable than any would have assumed when he arrived in Manhattan twenty years ago, a talent from New Orleans whom musicians such as Buster Williams were telling everybody about after they heard him in his hometown. “There’s a boy down in New Orleans who’s going to upset everybody when he comes to New York,” Buster said.

What Marsalis became went far beyond what anyone thought was in the offing, even those most impressed by his enfant terrible stage. As Woody Shaw told Maxine Gordon: “He’s going to go beyond all of us, not just on the horn but in the music. he’s going to take it some place else. I can hear it.” Shaw was right. His impact was to go far beyond the level upon which he could play his horn at eighteen years old. Easily he most totally gifted trumpeter to arrive since 1960, he was described in the middle eighties by Ron Carter as the best player to have appeared in the last fifteen years. That was because, by 1970, things were beginning to go bad for jazz. The phenomenon of fusion was on the build and it was debunking swing, in all its magnificent variety, through static rock and funk beats, electric pianos, and bass guitars. At the same time, so-called avant-garde jazz of the sort distinctly separate from the swinging version that Ornette Coleman brought to New York in 1959 had dispensed with jazz rhythm altogether. Major figures in jazz either sold out to pop trends or abdicated while those with serious integrity continued to swing in contexts of increasing obscurity. Those given to premature autopsies were sure that, this time, jazz was on its death bed. So when Marsalis moved north to New York in 1979, things looked fairly grim for jazz because, in terms of aesthetic troops, younger musicians didn’t seem to have much interest in the true identity of the art.

Marsalis changed that situation dramatically. By example, through recruitment, teaching, and his own accomplishments, he became, as Betty Carter said, “the fate of the music. I believe he arrived here to bring the music back.” As the youngster developed and his vision clarified, he went on to become both the Dizzy Gillespie and the Duke Ellington of his generation. He created a new plane of technique and rhythmic complexity for his instrument as Gillespie had and went on to compose perhaps the most wideranging and impressive body of music since the death of Ellington. Like Gillespie, the swing-struck lad from the land of red beans and rice also possessed the missionary zeal to gather and encourage other musicians. He would talk them into coming to New York and help them maintain morale once they got here. This Gillespie redux was given to showing these young musicians many technical things and, as is own comprehension deepened, Marsalis urged them to learn the entire language of the music, not just the superficial sound of it. The four major drummers of their generation are Kenny Washington, Lewis Nash, Jeff Watts, and Herlin Riley; half of them, Watts and Riley, came to power in ;Marsalis’ band. Pianists Kenny Kirkland, Marcus Roberts, Stephen Scott, Cyrus Chestnutt, Eric Reed, and Farid Barron have come through there. Alto saxophonist Wes Anderson, tenor saxophonists Don Braden, Todd Williams, James Carter, Walter Blanding, and Victor Goines have been in that band of his. Bassists Charnette Moffett, Lonnie Plaxico, Bob Hurst, Reginald Veal, and Ben Wolf have had to handle their register in the rhythm section. Not a lightweight list. For the premier performance, the recording, and the road tour of Marsalis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Blood On the Fields, the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra was dominated by personnel brought from across the country whom the composer had encountered in master classes he had given when some of them were little more than children.

That level of engagement with music and musicians never gave in and maintains itself to this second. While such devotion was expected of Art Blakey and Betty Carter, it was surprising from young Marsalis, whose home was always filled with young musicians talking about music or going to the piano or practicing, some sleeping in the bathtub of his first apartment, others calling rom places like Detroit to learn certain harmonic sequences and the sounds of particular chords, which he played for them over the telephone. Like a contemporary Ellington, he turned his back on the ragamuffin minstrelsy of the fusion period and his sartorial example got most musicians out of coming on bandstands ragged up as though they were rehearsing in somebody’s funky basement or were dressing the part to get a job with a rock band.

While the technical expansions of his art, the reiteration of virtuosity, and the reassertion of bandstand elegance were not met happily by the critical establishment, that made no difference to an international audience of listeners, who knew almost immediately that something special was afoot. Besides, those listeners did something that few jazz writers do: they went out to hear music and stuck around, listening throughout the night whenever possible. Sometimes these listeners traveled to the Vanguard from as far away as Minnesota in order to hear Marsalis and his players, or they went every year from Detroit to Washington, D.C. when he was doing engagements at Blues Alley as Christmas and the New Year approached.

Celebration was the name of the game and every night had a festive quality to it because the sound of welcome and of support, the essential feelings of jazz, were in the air. Marsalis recalls that when Herlin Riley joined the band, that the deep connection to the humanity of New Orleans started to assert itself in the way all of the musicians dealt with each other. This gave the music itself the same kind of quality one experienced when a New Orleans girl gave a party for the band one night on New York’s Upper West Side and the food, the music, and the human interplay made one realize that the warmth and style Louis Armstrong always remembered so fondly were still firmly in place. That warmth and style were extended by the audiences. The listeners were often well-dressed and classy, the guys good looking and the women sometimes fine enough to redefine fine. Audiences packed the clubs and were lined up outside the Vanguard until 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning, thrilled to get in and given to joyous shouting, whistling, and clapping, as the music lifted up. These kinds of reactions were much deeper than the promotional power of a record company, which cannot sustain the audience of someone whom the listeners don’t like. If record companies could make audiences do whatever they wanted them to do, there would be much more profit because anybody foisted on the public could remain a star over the years instead of, in regular fashion, becoming just another lucrative flash in the pan, here yesterday, gone today, sometimes rich, almost always forgotten.

As the breadth, substance, and depth of Marsalis’s work makes clear, he will be remembered long after his most irrational detractors are forgotten. Gifted enough to conquer both jazz and European concert music, going to the top in both idioms–an achievement that has no precedent–he has also chosen to play jazz itself, not a style of jazz, which means that he has had to develop authority in approaches that range from New Orleans to the best work of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane as well as the Miles Davis Quintet featuring Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. The upshot is that Marsalis the bandleader and composer, like Charles Mingus, John Lewis, George Russell, and Horace Silver at their finest, became fascinated with the challenge of breaking out of conventional forms while maintaining the strengths and subtleties of the blues, of swing, and the counterpoint that arrived from New Orleans, not Europe.

In order to thoroughly address the weight of the music, Marsalis had to turn his back on the car dealer mentality that dominates so much of jazz discussion in magazines. The people given to this mentality, all willing to promote the sale of anything eccentric, whether it drives well or not, are part of a jazz car dealership clan that has a thirty-five-year intellectual tradition of crumbling under innovation the word, not innovation the fact. While the car dealers were looking the other way, Marsalis applied his talent with such originality that he became, album by album and public performance by public performance, the most important innovator to arrive in jazz since the middle sixties. He rethought the playing of this instrument, the harmony, the rhythm, and the nature of composition with such expanding authority across layerings of reinvented style that his output now seems beyond the capabilities of one person.

Those achievements are, in fact, beyond a single individual. Art historian Kenneth Clark could have been writing about Marsalis when, in What Is A Masterpiece?, he discussed two aspects of a transcendent work, describing them as a confluence of memories and emotions forming a single idea, and a power of recreating traditional forms so that they become expression of the artists epoch and yet keep a relationship with the past. This instinctive feeling of tradition is not the result of conservatism, but is due to the fact that, in Lethaby’s familiar words, slightly adapted, a masterpiece should not be “one man thick, but many men thick.”

Marsalis himself points out that none of what he has achieved would have been possible without a whole heap of gracious instruction in the musical specifics of various styles, not nebulous rhetoric. Those specifics were presented to him both on the bandstand and in conversation with musicians such as Danny Barker, Lionel Hampton, Sweets Edison, Roy Eldridge, Joe Wilder, Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, Walter Davis, Jr., Charlie Rouse, Jimmy Heath, Frank Foster, John Lewis, Art Blakey, Elvin Jones, Barry Harris, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams, Ornette Coleman, Ed Blackwell, James Black and, of course, his father, Ellis Marsalis, the legendary New Orleans jazz teacher and smoking piano player.

Coming in contact with those musicians and many others, Marsalis was able to see clearly the size of the art he had chosen. He came to understand the scope of the music, beginning with his horn. From close study of recordings and from discussions with other trumpeters he digested a vocabulary that might now be the broadest in the history of jazz trumpet. In that sense, the actual magnitude of Louis Armstrong was a revelation in terms of tone, melody, rhythm, and giving a form to improvisation. Marsalis was so thorough in what he learned that, in the dressing room of the now defunct New York club Lush Life, he took Don Cherry’s pocket trumpet and began playing improvisations the older musician had created on Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come. Everything that Marsalis took seriously, each thing that had added to the expressive palette of the music, contained with Kenneth Clark pinpointed when he wrote, “Effective revolutions depend on convincing details.”

The maturing power of those effective details is what has made the career of Marsalis such a surprising voyage. In the middle eighties, when he began reinventing New Orleans music on Black Codes, the bass line of the title track coming from the Crescent City street theme, “Hey Pockee Way.” With that recording, pianist Anthony Wonsey says: “He changed jazz. It was some new stuff, no matter what anybody says. But they know. We all listened to that. It was something different, different from Miles, Wayne, Herbie, from everybody. He set a new direction and everybody was listening to it.” Alto saxophonist Jon Gordon observes that: “From Black Codes forward, Wynton obviously became one of the greatest arrangers for small groups in the history of jazz. Anybody with ears can hear that. His writing for his small groups is just incredible.”

Those reinventions continued through his reduction of his band from a quintet with his brother Bramford to a quartet featuring Marcus Roberts, which rewrote the book on avant-garde trumpet, piano, and rhythmic complexity on Live At Blues Alley. In the quintet with Todd Williams, Marsalis continued to explore his favorite area, the blues, the high point of that band captured on the remarkably structured recording, Uptown Ruler. His sextet with Wes Anderson produced the marvelous Levee Low Moan, followed by The Majesty of the Blues, which first laid down the broad aesthetic scope that Marsalis has continued to develop. The depth of the connection to the soul sources of the music are quite evident on the “Uptown Ruler” included on this Vanguard set, where the chanting and singing move us into the life of the night and the sensuality that underlies the proud intelligence.

Marsalis has–since the Classical Jazz series that was conceived by Alina Bloomgarden began at Lincoln Center in 1988–been Artistic Director of what later became Jazz at Lincoln Center in 1991, the most important jazz program in the world. His programming choices and the amount of preparation have resulted in dozens upon dozens of superb performance,s featuring as examples of the sweep of the personnel, trumpeters from Doc Cheatham, Sweets Edison, Dizzy Gillespie, and Art Farmer to Don Cherry, Wallace Roney, Nicholas Payton, and Roy Hargrove. Under the executive direction of the indefatigable Rob Gibson and an expanding staff, the program has become, since 1994, the first full-fledged jazz constituent at a major American arts complex, standing there equal with ballet, opera, film, and theater. There are commissions, lectures, film programs, master classes, national and international tours, concerts for young people, and a national big band competition. Starting in 1989 as the Classical Jazz Orchestra, The Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra is now ten years old and, as proven on Big Train and Sweet Release/Ghost Story from this massive release of Marsalis music, it has become the best orchestra of its kind on the planet. Without Marsalis, none of this would have been possible.

Bassist Peter Washington, who is but thirty-five and has played on more than two hundred albums, says of Marsalis: “No one can deny that he has brought much more respect to jazz as an art. Anybody out here can feel the difference. Wynton is responsible for a new level of respect, here and around the world. He also has a phenomenal work ethic. He keeps developing and working at his craft and writing long pieces, when he wants to, that make plenty of musical sense. The backlash against him is proof of how much good he has done out here. If he wasn’t so good for the music nobody would care about him.”

These recordings, all seven of them, provide a mythical seven nights at the Village Vanguard, since no band works there Monday through Sunday and since the personnel switches back and forth between bands with Todd Williams and Marcus Roberts as opposed to Victor Goines and Eric Reed. But that is all part of what makes this such an imposing set of performances. One can see that this band, with either personnel, was one of the greatest not only of its time but of all jazz time. As “Pedro’s Getaway” lets you know, the swing, the precision, the fire, and the originality of the music is often overwhelming. Much of this has to do with Marsalis himself, whose opening version of “Cherokee” changes the record book as far as his horn is concerned and whose playing on “Black Codes,” “:Uptown Ruler” and “Jig’s Jig,” as but three examples, makes it clear, yet again, that he is the king of avant-garde trumpet firmly rooted in jazz, blues, and swing. Marsalis has pointed out before that his quite detailed familiarity with the European avant-garde language from his own performances of it in orchestras under the baton of men like Gunther Schuller determines his unwillingness to write or improvise what is called jazz but sounds like second rate imitations of twentieth century European music. The swelling fire with which he executes a number of the passages in those mightily adventurous improvisations recalls Roy Eldridge realigned by another time. His ballads speak for themselves. In fact, the extended “Embraceable You” sets forth new plans of lyric majesty and rhythmic intricacy.

Then there is the playing of the band itself. Both rhythm sections have very original ways of accompanying the featured improvisers, with Riley weaving together New Orleans street beats and his own inventive version of the jazz language. Veal, in his introductions to “Down Home With Homey” and “In The Sweet Embrace Of Life”–not to mention the stuff he whips out on track after track in the rhythm section–makes it inarguable that he is not only the great power bassist of his ear but the one with the most unique set of syncopations and ideas he used to create swinging counterpoint. Ben Wolfe, by the way, is not even vaguely playing around either, always attacking the bass with his own drive and sense of counterpoint. That counterpoint is worked at variously by perhaps the two most impressive piano players of the last decade and a half, Marcus Roberts and Eric Reed, each of whom invents with rhythmic daring and originality of the sort that takes up the slack and expands upon the improvised, orchestral arrangement from the piano in the rhythm section that Ellington, Monk, Lewis, and Silver brought to such profound authority. As–to just pick two–his features on “Down Home With Homey” and “Pedro’s Getaway” underline, Wes Anderson is the main man on his instrument in his generation, the alto player slept on the longest but the one who keeps lighting up the music with ever higher stacks of flaming logs. Williams and Goines are equally impressive and Wycliffe Gordon is acknowledged among musicians as the young master of what he does with that trombone. In all, these are kinds of musicians who make audiences jump and shout, which they did nightly at the Village Vanguard. There were no houses more awed than those who sat there as the first section of “Citi Movement” was played, exhibiting a kind of ensemble virtuosity that, given the length of the performance, sets another standard for group playing. Oh, yeah.

If you weren’t there, you missed some of the champion jazz playing of any era. But you have this document in your hands. It will take you back to a mythical place and a mythical time, one filled with hot and sweet music, people packed in like sardines, and women who made solid all of the metaphors in the most beautiful and lyric moments of the invisible activity on the bandstand. What can you say? I guess no more than Marsalis himself often says when he hears a strong performance: “It was swinging. It started off swinging. It kept swinging, and those who heard it will remember it.”

– Stanley Crouch (September 1999)

Credits

Produced by Steve Epstein

Recording engineers: Tim Geelan, 1990-1991; Mark Wilder 1993-1994

Recorded by: National Public Radio for the series: “Wynton Marsalis: Making the Music” – Steve Rathe, John Stelluto, Michael Schweppes, Margaret Howze, John Harris, John Carrillo, Brian Kingman.

Mixing Engineer – Todd Whitelock

Edited and Assembled by Delfeayo Marsalis at the Park Hyatt, Los Angeles, Suite 808

Mastered by Delfeayo Marsalis at The Empire Hotel, NYC, Suite 1020

Additional Mixing by Patrick Smith and Jalmoose

Pro Tools engineering: Michael Cyr

Remote Recording Facilities: Sheffield Remote Recording 1990-1991; Record Plant Remote Recording, 1993

Mixed at Sony Music Studios, NYC

Production Coordinator: Dennis Jeter

Art Direction: Wynton Marsalis, David Ellis and Erwin Gorostiza

Illustrations: David Ellis

Design: Erwin Gorostiza

Booklet Photography: Frank Stewart (portraits), David Ellis (all others)

THANK YOU:

Wessell Anderson, Todd Williams, Wycliffe Gordon, Marcus Roberts, Reginald Veal, Herlin Riley, Victor Goines, Eric Reed, Ben Wolfe, Steve Epstein, Jalmoose, Ed Arrendeil, Billy Banks, Todd Whitelock, David Robinson, Matt Dillon, Genevieve Stewart, Dennis Jeter, Ron Carbo, Lorraine Gordon, Gabrielle Armand (big time!), Denise Gatto, Erwin Gorostiza, Dave Ellis, Susan Levin & Laura Sanano, Marilyn Laverty, Seth Cohen, Jim Flammia & everyone at Shore Fire Media, Rob Gibson & everyone at Lincoln Center, Stanley Crouch, Frank Stewart, Murray Horwitz, Margaret Howze, Bettina Ownes and the entire NPR “Making The Music” staff.

-WYNTON MARSALIS

Wessell Anderson is a Leaning House Artist.

Victor Gaines appears courtesy of Rosemary Joseph Records.

Wycliffe Gordon appears courtesy of Nagel-Hayer Records.

Eric Reed appears courtesy of The Verve Music Group.

The Management Ark

Edward C. Arrendell II • Vernon H. Hammond III

Band 1 (Recording dates: March 9-10, 1990; July 3-7, 1991)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet)

Wycliffe Gordon (trombone)

Wessell Anderson (alto saxophone)

Todd Williams (clarinet, tenor and soprano saxophone)

Marcus Roberts (piano)

Herlin Riley (drums)

Reginald Veal (bass)

Band 2 (Recording dates: December 3-4-5, 1993)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet)

Wycliffe Gordon (trombone)

Wessell Anderson (alto saxophone)

Victor Goines (clarinet, tenor and soprano saxophone)

Reginald Veal (bass)

Eric Reed (piano)

Herlin Riley (drums)

Band 3 (Recording dates: December 2-3-4, 1994)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet)

Wycliffe Gordon (trombone)

Wessell Anderson (alto saxophone)

Victor Goines (clarinet, tenor and soprano saxophone)

Ben Wolfe (bass)

Eric Reed (piano)

Herlin Riley (drums)

DISC 1 Monday Night

1. Welcome #1

2. Cherokee

(Ray Noble)

Peter Maurice Music Admin. by Shapiro Bernstein & Co. (ASCAP)

BAND 2

3. The Egyptian Blues

(Wessell Anderson)

Copyright Control

BAND 1

4. Embraceable You

(George Gershwin / Ira Gershwin)

WB Music Corp. (ASCAP)

BAND 3

5. Black Codes From the Underground

(Wynton Marsalis)

6. Harriet Tubman

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 1

7. Monk’s Mood

(Thelonious Monk)

Embassy Music Corp. (BMI)

BAND 3

8. And the Band Played On

(Wycliffe Gordon)

Coud de Cone Music, Inc. (ASCAP)

BAND 1

9. The Cat In The Hat Is Back

(Todd Williams)

Copyright Control

BAND 1

10. Set Break

BAND 1

DISC 2 Tuesday Night

1. Welcome #2

2. Uptown Ruler

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 2

3. Down Home With Homey

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 1

4. Reflections

(Thelonious Monk)

Thelonious Music Corp. (BMI)

BAND 3

5. Jig’s Jig

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

6. Sometimes It Goes Like That

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 2

7. In A Sentimental Mood

(Duke Ellington)

Famous Group Corp. (ASCAP)

BAND 1

8. Knozz-Moe-King

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

9. (Set Break)

BAND 1

DISC 3 – Wednesday Night

1. Welcome # 3

2. Buggy Ride

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

3. I’ll Remember April

(Gene DePaul / Patricia Johnson / Don Raye)

Universal-MCA Music Publishing / Rytvoc, Inc. (ASCAP)

BAND 3

4. Stardust

(Hoagy Carmichael / Mitchell Parish)

EMI Mills Music (ASCAP) / PSO Limited (BMI)

Band 3

5. In The Court of King Oliver

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

6. Bona & Paul

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 1

7. Four In One

(Thelonious Monk)

Thelonious Music Corp. (BMI)

BAND 1

8. Way Back Blues

(Count Basie)

WB Music Corp. (ASCAP)

BAND 3

9. Rubber Bottom

(Duke Ellington)

Famous Group Corp. (ASCAP)

10. Where’s The Music?

(Duke Ellington)

Famous Group Corp. (ASCAP)

BAND 3

11. Play The Blues And Go

(Duke Ellington)

Famous Group Corp. (ASCAP)

BAND 3

12. (Set Break)

BAND 3

DISC 4 Thursday Night

1. Welcome #4

2. Pedro’s Geaway

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

3. Evidence

(Thelonious Monk)

Thelonious Music Corp. (BMI)

BAND 3

4. Embraceable You

(George Gershwin / Ira Gershwin)

WB Music Corp. (ASCAP)

BAND 1

5. A Long Way (aka: Dark Heart Beat)

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 2

6. The Arrival

(Marcus Roberts)

WB Music Corp. (ASCAP)

BAND 2

7. Misterioso

(Thelonious Monk)

Thelonious Music Corp. (BMI)

BAND 1

8. Happy Birthday

(Traditional)

BAND 1

9. The Seductress

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 2

10. (Set Break)

BAND 2

DISC 5 – Friday Night

1. Welcome #5

2. The Majesty of The Blues

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 1

3. Flee as a Bird To The Mountain

(Traditional Hymn)

BAND 2 with Dr. Michael White (clarinet)

4. Happy Feet Blues

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 2

5. Thelonious

(Thelonious Monk)

Thelonious Music Corp. (BMI)

BAND 3

6. Stardust

(Hoagy Carmichael / Mitchell Parish)

EMI Mills Music (ASCAP) / PSO Limited (BMI)

BAND 3

7. Intro to Buddy Bolden

8. Buddy Bolden

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

9. Swing Down Swing Town

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

10. Bright Mississippi

(Thelonious Monk)

Thelonious Music Corp. (BMI)

BAND 2

11. Set Break

BAND 2

DISC 6 Saturday Night

1. Welcome #6

2. Citi Movement

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

3. Winter Wonderland

(Felix Bernard / Dick Smith)

WB Music Corp. (ASCAP)

BAND 2

4. Brother Veal

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 2

5. Cherokee

(Ray Noble)

Peter Maurice Music Admin. by Shapiro Bernstein & Co. (ASCAP)

BAND 1

6. Juba and A O’Brown Squaw

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

DISC 7 Sunday Night

1. Welcome #7

2. In The Sweet Embrace of Life

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 2

3. Local Announcement

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

4. Altar Call

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

5. Final Statement

(Wynton Marsalis)

Skayne’s Music (ASCAP)

BAND 3

Personnel

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Todd Williams – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

- Ben Wolfe – bass

- Marcus Roberts – piano

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Eric Reed – piano

- Dr. Michael White – clarinet

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Cherokee - JLCO with Wynton Marsalis at BBC Proms 2002

-

Videos

Videos

Play The Blues And Go - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Warsaw (1994)

-

Videos

Videos

Way Back Blues - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Warsaw (1994)

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton Marsalis Septet at Umbria Jazz 1993

-

Videos

Videos

Play the Blues and Go - Wynton Marsalis Septet live on the lawn of the White House

-

Videos

Videos

And The Band Played On - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Berlin (1989)

-

Videos

Videos

Where’s The Music - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Berlin (1989)

-

Videos

Videos

Chasin’ The Bird - Wynton Marsalis Sextet at Newport Jazz Festival 1989