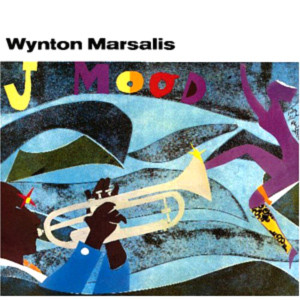

J Mood

Recorded in December 1985, J MOOD heralds the start of a second phase in Wynton’s career and the formation of a new band featuring the “J Master,” Marcus Roberts, on piano. Wynton’s evolving collaboration with the “J Master,” which continued through the early 1990s, has already become a landmark in recent jazz history. Bob Hurst’s impeccable bass lines and Jeff “Tain” Watts’ mercurial drumming complete the line-up.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quartet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | October 14th, 1986 |

| Recording Date | December 17-20, 1985 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | CK 40308 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| J Mood | 8:33 | Play |

| Presence That Lament Brings | 5:54 | Play |

| Insane Asylum | 6:34 | Play |

| Skain’s Domain | 6:31 | Play |

| Melodique | 4:31 | Play |

| After | 6:11 | Play |

| Much Later | 4:38 | Play |

Liner Notes

For Wynton Marsalis, the J Mood expresses everything from gutbucket to ethereal passion. On one hand, it is the ruminative repose that follows the intimate dialogue of actual romance, the sweet silence and soft breathing after the act of love. On another, it is the kind of clarity that comes of solitude and provides the resolve that makes for refinement. The bittersweet knowledge of the aches and soothings of life is also part of the J Mood. Raw or smooth in intensity, J Mood is the suave soul at the center of swing. Further, J Mood is finesse, proof that elegance is the most sublime manifestation of vitality.

It is the startling finesse – whether flying or loping, strutting or easing along – that makes J Mood yet another step up to higher ground for Wynton Marsalis. There is a clear extension of the victories that made for such strong music on his previous album, Black Codes (From The Underground). The thematic continuity, the harmonic adventure, and the uncontrived freedom of phrasing within forms are even more impressively functional in his present quartet. This is obviously the work of musicians who have spurned the misconceptions that abound in the contemporary jazz world, where pop forms, ineptitude, and trivial trends are discussed with a sociological seriousness that avoids the issue of artistry and of professional levels of technical control. Sellouts are applauded and frauds are showered with explanatory ink. Fumbling or pretentious eccentricities are misconstrued as innovative.

But the freshness brought to blues, ballads, and swing on this collection results from a commitment to craft inspired by musicians like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk. Such artists knew the J Mood from the chitlin switch to the penthouse, and they also made music in which much more was going on than initially met the ear of the surface listener. Close attention to the paling on this compact disc will show how the band approaches form with adventurous grit, making collective shifts of rhythm, meter, and tempo that reveal a serious rethinking of call-and-response, polyrhythm, and syncopation. In color and subtlety this music is in the line of the blue mood (as opposed to literal blues) introduced by Ellington in pieces like “Solitude.” On the faster pieces, there is the rhythmic grilling of phrases that projects the joyous spunk in face of the demands of improvisation that Armstrong meant when he said, “Oh you dog. Boy, if I ain’t riffing this evening. I hope something!”

In his feature on “Skain’s Domain,” Marsalis shows that he is not only the hardest swinging of the younger trumpet players, but that he is working toward a rhythmic complexity that builds upon the monumental implications of Dizzy Gillespie and the bold Don Cherry of The Shape Of Jazz To Come. The liberation with which Marsalis changes speeds and meters inside his lines, toys with accents, and maintains thematic material on every level – melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, and textural – has little precedent in music so attentive to form. But what gives the performance so many stirring thrusts is the group interaction, the skill with which these players have moved the music beyond the single horn line superimposing meters to a stunning collective flexibility. What they do results in phrases being heard as numbers of beats instead of rigid meters. A four-bar phrase can be approached as sixteen quarter notes played as two bars of five/four and two of three/four, or four bars of three and one of four, and so on. However academic that might sound, it doesn’t reduce the pleasure of the transmuting swing that results from the metric modulations, nor does it make the innovative potential of such group playing less impressive. Given the downbeat resolutions of these rhythmic games, this music has a tension and release that moment-to-moment “avant garde” playing never does. A wonderful example of the group’s attentiveness is how the dynamic change in the middle of Marsalis’s feature deftly dissolves into a collective waltz before returning to the faster four/four tempo. For those interested in the structure, the song is twenty-seven bars long, with a two/four measure at the nineteenth bar.

With a tone rounder and more clarion than ever, Marsalis displays a deepening blues sensibility on the title track. His improvisation is almost purely melodic, benefitting from his and the group’s sensitivity to contrasts of volume and attack. Over a loping groove in which piano, bass, and drums brilliantly play with the beat, Marsalis twirls daring phrases of off-center rhythms, elemental indigo attacks, and unpredictable accents. Pianist Marcus Roberts improvises a statement of wonderful thematic control for a man in his early twenties. The material he sets up in his first chorus – the phrasing, the chords, and the little fragment of blues melody that begins at the ninth bar of that first chorus – is held onto and extended with invention and deep blues feeling. The grasp of form that allows Roberts to make so much of that little tissue of blues melody and the figures that follow it, the attention to texture, and the swing prove the pianist to e a talent from whom we should hear much. But his rhythm section playing shouldn’t be overlooked. Notice the metric mobility and the rhythms he uses in what amounts to almost a conversation between trumpet and piano on “Skain’s Domain,” as but one example.

But Hurst, like Roberts, is a great addition to the group. He already knows how to walk lines that are as melodic as they are harmonic and rhythmic. Hurst seems to hear the single quarter note in eighth-note triplet or sixteenth-note subdivisions, allowing him either three or four places where he can start his phrase and still be inside the meter. Such attention to detail gives great variety to the feeling of his beat. Hurst’s work on “Skain’s Domain” is nearly a definition of what young bassists will have to deal with, will have to absorb in their own personalities. There he plays with such fluidity of idea, tempo, and meter; of counterpoint, harmonic verve, and texture. And his impressive technique is in the service of freedom of expression. Above all, as the title track shows, he knows the meaning of swing in the motion of the blues, and indispensable element of jazz knowledge and jazz feeling.

Since the first Wynton Marsalis album, Jeff Watts has been developing what is now the most inventive style of all younger drummers. Displacement is his middle name and swing is where his drumming lives. Watts is a master of texture, extremely knowledgeable of the colors that can be gotten from drums and cymbals. It is interesting to note how well his explosions on “J Mood” make such cunning use of the sustaining powers of the firmly struck cymbal. In Watts’ style that is something akin to a held note. Metric modulation gives him no trouble and, as his work on “Insane Asylum,” “Skain’s Domain,” and the concluding blues shows, Watts can give very different pulsations to quick tempos. Like all the great drummers, Watts expresses a sensitivity to lyric rhythm and timbre on the ballads that heightens the lilt of the mood or gives greater dimension to the melancholy.

As a unit, all four of these men are examples of the discipline and feeling that make jazz our most difficult performance art. They also form part of the reaction against the arrogant sloth and snarling decadence that face us all, threatening to devour all craft and purity, and to push human beings into the hopper of hysteria, where they will be stripped of all but obvious responses. In that sense, J Mood is a declaration of war against the contrived and the worthless. Like all that refers to the bittersweet richness of human value, this disc is a statement of elegance and of optimism, of compassion and of pride. At its best moments, J Mood shows how safe the warm soul of jazz is in the winter of our world.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

PRODUCED BY Steve Epstein

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER: George Butler

CHIEF ENGINEER: Tim Geelan

ASSISTANT ENGINEER: Dennis Ferrante

Recorded digitally at RCA Studio A, NYC – December 17-20, 1985 on the SONY PCM3324 Digital System through an MCI console

REMIX ENGINEER: Tim Geelan

Remixed at CBS Studios, NYC through a Neve Automated Console

Principal Microphones:

Neuman: U67, KM84

AKG414 EB-P48, C451

Electro Voice—RE55

Monitor Speakers: B&W 801

Mastered at CBS Studios, NY by Vlado Meller

Cover Illustration: Romare Bearden

This Compact Disc is digitally recorded and mastered.

MUSICIANS:

Wynton Marsalis, trumpet

Marcus Roberts (“J Master”), piano

Robert Leslie Hurst III, bass

Jeff “Tain” Watts, drums

MANAGEMENT: Edward C. Arrendell

ARRENDELL MANAGEMENT GROUP

Blair Plaza

1401 Blairmill Road

Suite 503

Silverspring, MD 20910

SPECIAL THANKS TO:

Romare Bearden, Al Murray, Steve Epstein, Cheem Geelan, George Butler, Genevieve Stewart

Personnel

- Bob Hurst – bass

- Marcus Roberts – piano

- Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums