Blood on the Fields

Risk exposing your ears to the first notes of BLOOD ON THE FIELDS, hear the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra wail through “Calling the Indians Out,” the opening invocation to the spirit of the first people whose blood soaked American soil in the long, painful birth of the American republic, and you’ll sit spellbound to the echo of the last note of Wynton Marsalis’s epic oratorio on slavery and freedom. Telling the story of two slaves, Jesse and Leona, it carries us along on their difficult journey to freedom, a journey in which they, and by implication all of us, must move beyond a preoccupation with personal power and learn that true freedom is, and must be, shared.

In 1997 Wynton Marsalis became the first jazz musician ever to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his epic oratorio Blood On The Fields. During the five preceding decades the Pulitzer Prize jury refused to recognize jazz musicians and their improvisational music, reserving this distinction for classical composers. In the years following Marsalis’ award, the Pulitzer Prize for Music has been awarded posthumously to Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane.

Album Info

| Ensemble | JLCO with Wynton Marsalis |

|---|---|

| Release Date | June 17th, 1997 |

| Recording Date | January 22-25, 1995 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | CXK 57694 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz at Lincoln Center Recordings |

| Digital Booklet | Download (pdf, 10 MB) |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| CD 1 | ||

| Calling The Indians Out | 5:27 | Play |

| Move Over | 10:04 | Play |

| You Don’t Hear No Drums | 11:50 | Play |

| The Market Place | 6:03 | Play |

| Soul For Sale | 6:08 | Play |

| Plantation Coffle March | 10:42 | Play |

| Work Song (Blood On The Fields) | 8:30 | Play |

| CD 2 | ||

| Lady’s Lament | 6:17 | Play |

| Flying High | 2:05 | Play |

| Oh We Have A Friend In Jesus | 4:06 | Play |

| God Don’t Like Ugly | 8:04 | Play |

| Juba And A O’Brown Squaw | 6:07 | Play |

| Follow The Drinking Gourd | 2:21 | Play |

| My Soul Fell Down | 2:20 | Play |

| Forty Lashes | 7:30 | Play |

| What A Fool I’ve Been | 2:33 | Play |

| Back To Basics | 11:29 | Play |

| CD 3 | ||

| I Hold Out My Hand | 7:38 | Play |

| Look And See | 5:08 | Play |

| The Sun Is Gonna Shine | 2:18 | Play |

| Will The Sun Come Out? | 9:13 | Play |

| The Sun Is Gonna Shine | 6:42 | Play |

| Chant To Call The Indians Out | 3:59 | Play |

| Calling The Indians Out | 5:36 | Play |

| Follow The Drinking Gourd | 1:47 | Play |

| Freedom Is In The Trying | 2:47 | Play |

| Due North | 5:36 | Play |

Liner Notes

WHOSE BLOOD, WHOSE FIELDS?

Sometimes it happens. A great thing rises before us and we all seem to know what it means at exactly the same time. This took place on the stage of Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center in New York City, a town where people work at not being impressed. Blood On The Fields. Uh oh. Something serious. The title tells you that. Something serious. Better get ready. Strap yourself in. The rhythm and tune of this ride might be rough. But it might also be beautiful.

Because of the historical importance of the premiere of Blood On The Fields, these liner notes contain an adaptation of the original program notes and the comments that Wynton Marsalis made on his bog work and its meaning. Nothing quite like it had ever been written, either by a jazz musician or one from another discipline. It was fitting that the opening was on April Fool’s Day, 1994, because Marsalis went beyond all that even those who most admired his writing expected of him. He reached a level of expression arrived at by only the very great artists, but the composer had achieved his new position through absolute contact with the mud and swamp water of the earth. At every turn, no matter how abstractly he might have handled his themes,, his rhythms, and his orchestration, there was always something inside the writing that was very old and very profound, something that drew upon the vitality of the Negro spirituals and the blues, those musics of spiritual concern in religious and secular contexts.

Blood On The Fields was sold out both of its two nights, with many standing outside the hall hoping they might convince others who had seats to sell one or two of their tickets. One would have thought money was being given away inside, so frantic were some of those trying to get in for a seat, for standing room only, for anything. That excitement put another layer of heat into the incipient spring night. The audience reflected the ethnic variety of Manhattan as well as the universal appeal of the music. As George Kanzler of the Newark Star Ledger reported, “It was one of those rare concerts where you knew something magnificent, even history-making, was taking place. At intermission, the audience was buzzing with excitement and by concert’s end there was a palpable feeling of awe, of being almost overwhelmed by the sheer power of the music.”

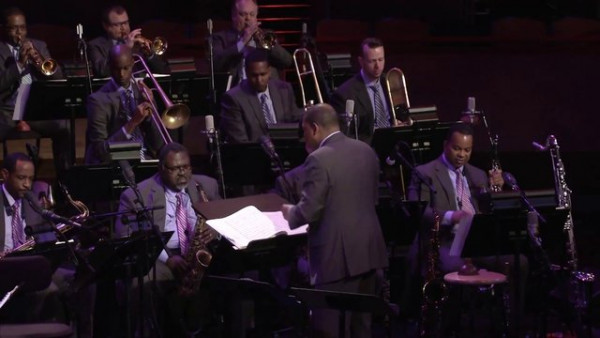

The epic length of the piece, nearly three hours, put it in a category beyond all other jazz composition. Where many had fumbled before him, either out of a lack of compositional skill or a tendency to pretension, Marsalis was showing how well all of the elements of jazz and its antecedents could work together. Marsalis used a jazz orchestra comprised of young musicians whom he had known almost since they began playing, musicians who were once no more than novices showing up at clinics or backstage following performances. They rehearsed long past frustration and technical obstacles, leaving one rehearsal daunted, another more confident. There was much nervousness before the band came out to let the audience judge. The ensemble executed an extremely demanding score with valor and precision. Marsalis also utilized the marvelous singing styles of Jon Hendricks, Cassandra Wilson, and Miles Griffith, each a representative of a specific era in jazz singing and jazz knowing. Hendricks, Wilson, and Griffith reached levels of swing, tragedy, stoic lyricism, and anger that were much deeper than what one is accustomed to in our time.

At 32, Marsalis was doing his own turn on the use of many different styles that was the central technique Duke Ellington brought to such high order for his 1943 historical masterpiece, Black, Brown, And Beige. But when Ellington was 32 in 1931, neither he nor anyone else had written a work this ambitious. It wasn’t possible. Marsalis, arriving in our culture when he did, was able to draw on everything that came before Ellington and all that came in his wake. The result was that Marsalis, who had been in pitched battle with the critical establishment, won the writers over just as he did the audiences that stood shouting and clapping when the piece ended. The new York Times reported, “Wynton Marsalis’s skills have grown as fast as his ambitions and he is the most ambitious younger composer in jazz … his music holds on to jazz fundamentals–blues and ballads, swing and Afro-Caribbean rhythms, call-and-response–while abstracting them into fast-mutating collages. With Blood On The Fields, he also proves he can write melodies that sound natural for singers … Mr. Marsalis’s ensembles bristle with polytonality, dissonance and jagged, jumpy lines and countermelodies, but the rhythm section pushes them along as if they were dance music … He comes up with elaborate structures and musicianly abstractions, but he also encourages old-fashioned jazz pleasures: snappy riffs, strutting syncopations, repartee between sections, competitive solos and the bedrock of the blues.”

Blood On The Fields was the sort of conquest across the board that signals fresh possibilities in American art because, in a time of so much disorder, so many cliches, and such cynicism, the listener is enobled by the experience of the music.

WHO AIN’T A SLAVE?

The evolution of Wynton Marsalis as a composer is one of the forces that defines the quality of our American art. His body of work now stands above that of all but the most important writers of jazz music. Marsalis has taken on such a large position in the writing of jazz music because he is in possession of a very rich talent and has no difficulty perceiving what kind of a Western music jazz is. He understands how it combines European harmony and African-derived ideas about percussion, drawing its primary melodic sources from the uniquely American line of the blues on one hand and Negro spirituals on the other. he is also aware of the impact that jazz, blues, and spirituals had on the music of Tin Pan Alley and the impact Tin Pan Alley had on jazz.

One of the reasons Marsalis is so clear on the elements that give his art its identity is that he has not only worked with jazz masters of every style but has had wide and successful experience in European concert music, performing everything from Bach to the avant garde of the twentieth century (the work of composers such as Stravinsky, Bartok, Stockhausen, Zwillich, and Ralph Shapey). That rich background has given Marsalis a strong and thorough grounding, not a superficial perception of what constitutes modern music. This technical education has allows Marsalis to grow ever stronger over the last fifteen years. The consistent growth of his mastery has been documented on nearly twenty albums, each addressing the basics of jazz with compositional variety and adventure. Over and over, one hears how clearly he has brought his own voice to the fundamentals that have given commonality to the highly individual work of the finest jazz musicians–4/4 swing (fast, medium, and slow), the blues, ballads, and Afro-Hispanic rhythms (what Jelly Roll Morton heard as an essential “Spanish tinge”).

In Blue Interlude, he went beyond even the best jazz writers of the fifties and the sixties to create a form for a small group that lasted nearly forty minutes but maintained cohesion through thematic and harmonic control. In Citi Movement, his ballet score for Garth Fagan, he wrote a three-movement symphony for seven pieces, a two-hour work that had no precedent. In This House/On This Morning was commissioned by Jazz at Lincoln Center in 1992 and found Marsalis working within a structure based on the Afro-American church service, exceeding in quality and complexity previous jazz pieces that built their foundations on the music of the Negro church. In This House was a whole work, not a group of pieces that had no formal relationship to each other. For a collaboration with the New York City Ballet, Marsalis wrote Jazz (Six Syncopated Movements). It used riotous dissonance, marches, railroad train onomatopoeia, ballroom lines, and ragtime to give another form to the composer’s epic understanding of American life and history.

Tonight, we will hear Marsalis’s first extended composition for large jazz band. He calls it Blood On The Fields and explains that American slavery is its subject. Slavery was the buzzard pecking at the liver of the Constitution, and its shadow, like a dark virus, infected everything it touched. It made America schizoid, touched off increasingly hostile debate, challenged the Christian underpinnings of universal humanism, inspired the abolition movement, and made visceral every national shortcoming. That is why Marsalis is convinced that much of our identity as Americans is the result of what slavery meant to our country–its social contract, its laws, its politics, its literature, its military history, its theater, its film. The issues surrounding slavery led to the Civil War, to Reconstruction, and the ninety-year-long struggle to take the Constitution south, resulting in the Civil Rights Movement, our second Civil War.

But the subject of American slavery is much more than a tale of racial degradation. To leave it there is to trivialize what it meant and should mean. No, American slavery isn’t the rhetorical football that sentimentalists, hysterics, and demagogues so easily kick around. It was a long, tragic condition that continues to loom larger than almost all that has been said about it by those other than slaves themselves. As a genuine tragedy, slavery is a prismatic metaphor through which we can see beyond color by seeing all colors. American issues of labor, of gender, of the exploitation of children, and, finally, of human rights within this society are traceable back to that phenomenon, for it defined every inadequacy that was allowed to exist within the United States. The “peculiar institution” raised high the central issue facing civilization under capitalism, which is bringing together morality and the profit motive. Slavery also found in its opponents a deeper understanding of the meaning of democracy and inspired actions that helped define the ethical grandeur of courage within our culture. It is, therefore, a metaphor for every question of unfairness and every question of servitude. As Herman Melville wrote in Moby Dick, understanding this well, “Who ain’t a slave?”

Of the work, Marsalis says, “It starts on a slave ship during the middle passage. We meet two Africans, jesse and Leona, who until being forced into the equality of a tragic circumstance, occupied very different stations in life–he is a prince; she a commoner. They get sold to the same plantation and are chained together on a coffle. Jesse gets wounded trying to escape, and in order to survive the journey to his new home (for lack of a better term), he has to lean on Leona. When they arrive, he doesn’t even thank her for saving his life. He had been a prince in Africa, so perhaps it was beneath his noble station to express gratitude to a commoner. But one thing is apparent, he’s caught up in the injustice of his circumstance. For him, freedom is a purely personal thing. He needs to have his understanding expanded, and Leona is equipped with the tools to do the job.

“Eventually, Jesse goes to see Juba, a wise man posing as a fool. And Juba tells him that he needs to do three things. he has to love his new land, he has to learn how to sing with soul, and he has to learn who he will be when free–what will he call himself? nigger, colored, Negro, black, Afro-American, African-American or the next name (maybe just America). Juba’s advice sounds too “Uncle Tom-ish.” Jesse escapes and gets caught. He has a painful awakening under the bite of the lash. This convinces him to transform his attitude and ultimately his character.

“The transformation is completed when he sings the blues chant, “Oh, anybody hear this plaintive song. Oh, who wants to help their brother dance this dance? Oh, I sing with soul, heal this wounded land.”

Blood On The Fields details in music what I feel it takes to achieve soul: the willingness to address adversity with elegance.

– Stanley Crouch

Credits

I

Calling The Indians Out

Trouble in our own land, crimes against the human soul

far too large for any describing words to hold.

II

Move Over

In a slave ship that darkly sways beneath the star of democracy, Jesse and Leona lie.

A captured man and woman, Jesse and Leona.

Cassandra Wilson – Vocal

Wess Anderson – Alto Saxophone

Victor Goines – E-flat Clarinet

III

You Don’t Hear No Drums

Miles Griffith – Vocal

Wynton Marsalis – Trumpet

Eric Reed – Piano

IV

A. The Market Place

In teeming marketplaces, onto the sweet soil

of our democracy is poured the salt of a business

that gives a bitter taste to our national life.

Wess Anderson – Alto Saxophone

Vietar Goines – Clarinet

Wayne Goodman – Trombone

Robert Stewart – Tenor Saxophone

James Carter – Baritone Saxophone

B. Soul For Sale

Jon Hendricks – Vocal

V

Plantation Coffle March

Reborn in this land of plenty as livestock.

Talking work animals.

James Carter – Baritone Saxophone

Herlin Riley – Tambourine

VI

Work Song (Blood On The Fields)

Soon can mean ten minutes, or ten lifetimes.

In this case, 14 years of bondage has passed.

Wycliffe Gordon – Trombone

VII

Lady’s Lament

Victor Goines – Tenor Saxophone

A. Flying High

Russell Gunn -Trumpet

VII

Oh We Have A Friend In Jesus

0l’ Massa /s a good and righteous man.

He likes for his Negroes to worship and honor a merciful and just God.

A. God Don’t Like Ugly

They, however, interpret the word of God quite differently.

Wess Anderson – Alto Saxophone

Roger Ingram – Trumpet

Marcus Printup – Trumpet

Wycliffe Gordon – Trombone

IX

Juba And A O’Brown Squaw

Jesse thinks not of God, not of heaven, not of justice,

only his own freedom is on his mind. He goes to see Juba.

A man so wise, the uninformed think he is a fool.

Jon Hendricks – Vocal

X

Follow The Drinking Gourd

Jesse don’t care about no Indians, no land, no soul, no singing, and no Leona.

It was time for him to go ahead and run.

Reginald Veal – Bass

A: My Soul Fell Down

XI

Forty Lashes

If the opposition be truly serious, no matter how noble the heart or

just the cause, the unprepared will feel the bitter lash of failure.

Herlin Riley – Drums

Wess Anderson – Alto Saxophone

Vietar Goines – E-flat Clarinet

Eric Reed – Piano

XII

What A Fool I’ve Been

Knocks on the head, feet in the butt can beget recognition.

A. Back to Basics

Wynton Marsalis – Trumpet

Ron Westray & Wycliffe Gordon – Trombone Exchanges

Wess Anderson, Victor Goines, Robert Stewart and James Carter – Saxophone Exchanges

Marcus Printup & Russell Gunn ~ Trumpet Exchanges

XIII

I Hold Out My Hand

What has more meaning than pain? He wants to know what soul is?

XIV

Look And See

Now he wants to listen

A. The Sun Is Gonna Shine

Miles Griffith – Vocal

XV

Will The Sun Come Out?

Yes, but still the blues.

Erie Reed – Piano

XVI

The Sun Is Gonna Shine

But Jesse has learned how to play the blues.

Marcus Printup – Trumpet

Wess Anderson – Atto Saxophone

Robert Stewart – Tenor Saxophone

Ron Westray – Trombone

Victor Goines – Clarinet

Russell Gunn – Trumpet

XVII

Chant To Call The Indians Out

XVIII

Calling The Indians Out

XIX

Follow The Drinking Gourd

His mind is set on a freedom larger than himself. Jesse escapes again, this time with Leona.

XX

Freedom Is In The Trying

Even for the righteous, success is never certain

XXI

Due North

Produced by Steve Epstein

Recording Engineer: Mark Wilder

Recorded in the Grand Hall of the Masonic Grand Lodge, January 22-25, 1995

Recorded digitally onto the Sony PCM 3348 Tape Recorder

Mix Engineer: Todd Whitelock

Mix Assistant: Jen Wyler

Post-produced at Sony Music Studios, NYC

Mixed to the Sony PCM 800, utilizing the AD122 24-bit analog-to-digital converter through a Prizm interface

Location recording equipment provided by Effanel and Sony Music Studios

Assistant Engineers: John Harrison, James Biggs, Brian Kingman, Brian Faehndrich

Production Coordinator: Dennis Jeter

Mastered at Sony Music Studios, NYC

Cassandra Wilson appears courtesy of Blue Note Records

Marcus Printup appears courtesy of Blue Note Records

Wessell Anderson appears courtesy of Atlantic Recording Corp.

James Carter appears courtesy of Atlantic Recording Corp.

Eric Reed appears courtesy of Mo’ Jazz, a division of Motown Record Company, L. P.

Plantation Scene Photo: Collection of The New-York Historical Society

Blood on The Fields is composed and conducted by Wynton Marsalis.

All songs ©1997 Skaynes Music (ASCAP)

All right reserved. Used by Permission.

Blood on The Fields was commissioned by Lincoln Center for The Performing Arts, Inc. and performed at Lincoln Center on April 1&2, 1994, as part of its Jazz at Lincoln Center presentations.

THE MANAGEMENT ARK

Santa Fe, NM • Princeton, NJ

Edward C. Arrendell II • Vernon H. Hammond III

Art Direction: Josephine DiDonato

Personnel

- Jon Hendricks – vocals

- Cassandra Wilson – vocals

- Miles Griffith – vocals

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Walter Blanding – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Robert Stewart – tenor sax

- James Carter – baritone sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Russell Gunn – trumpet

- Roger Ingram – trumpet

- Marcus Printup – trumpet

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

- Wayne Goodman – trombone

- Ron Westray – trombone

- Michael Ward – violin

- Eric Reed – piano

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Work Song (Blood on the Fields) - JLCO with Wynton Marsalis

-

Videos

Videos

Calling the Indians Out (Blood on the Fields)- JLCO with Wynton Marsalis

-

Videos

Videos

The Sun Is Gonna Shine (Blood on the Fields) - JLCO with Wynton Marsalis

-

Videos

Videos

Blood on the Fields (Rehearsal) - JLCO with Wynton Marsalis

-

Videos

Videos

Back to Basics - Wynton Marsalis with “Jazz in Marciac Big Band” (2004)

-

Videos

Videos

Soul for Sale - JLCO with Wynton Marsalis featuring Jon Hendricks on “Sessions at West 54th”

-

Videos

Videos

Back to Basics - JLCO with Wynton Marsalis on “Sessions at West 54th”

-

Videos

Videos

TV News Clips: Wynton talking about his Pulitzer Prize winning “Blood on the Fields”