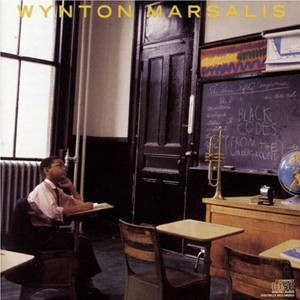

Black Codes (From the Underground)

One of the hardest swinging and best-loved of his 1980s recordings wraps listeners in the astonishing group sound that defined Wynton Marsalis. Firey performances by the players jazz writers dubbed “The Young Lions”: saxophonist Branford Marsalis, the “Doctone” – pianist Kenny Kirkland, the “Net Man” – bassist Charnett Moffett, drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts, and of course Wynton himself on trumpet.

Grammy Winner for “Best Jazz Instrumental Performance – Group.”

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quintet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | June 9th, 1985 |

| Recording Date | January 11-14, 1985 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | 468711 2 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Black Codes | 9:31 | Play |

| For Wee Folks | 9:06 | Play |

| Delfeayo’s Dilemma | 6:46 | Play |

| Phryzzinian Man | 6:44 | Play |

| Aural Oasis | 5:35 | Play |

| Chambers of Tain | 7:39 | Play |

| Blues | 5:21 | Play |

Liner Notes

As the cover tells you, it all comes down to knowing and wanting to know, to study and experience, to rebellion against the bondage of ignorance. And no major art can subsist on luck or on natural talent that is never put to the head-slapping test of discipline. So there is never a point at which learning and knowing don’t come together for the best expression of talent. The objective is mastery, which is always born of sophistication. In jazz, mastery has to do with an unavoidable velocity because the improvisor must work in a context where the moment is all. Where the recipe for shape, continuity, and form has to be conceived, mixed, cooked, and served immediately. As with all art, the more you know, the more you can do. And when everything is focused by integrity, you hear the emotion of idealism boiling over the top, spanning moods from the bristling to the frail tenderness of a vulnerable lover’s whisper. This recording has that scope of passion, and it is delivered with a gutbucket high-mindedness as intriguing as it is exciting, as infectious as it is soothing.

With Black Codes, Wynton Marsalis closes the door on high and low rabble ranting about his lacking a personal direction or the ability to express himself with entrancing emotion. Already, his tone, his phrasing, the notes he chooses and the harmonies included in his songs detail the imposing growth of a unique artists. That his work and the color of his music recall the contributions of seminal figures in jazz only means that he is part of a tradition, since the person who reminds the audience of no one has somehow managed to avoid the colossal problem of giving personal character to the essential particulars of an idiom.

He calls this album Black Codes (From the Underground) as a reference to the prohibitive 19th century slave laws that emphasized depriving chattels of anything other than what was necessary to maintain their positions as talking work animals. But Marsalis isn’t after whining or guilt-mongering. He is concerned with how those laws have evolved into contemporary trends and conceptions of both specific and universal implications. Marsalis sees the present problem as one in which too many have chosen to be no more than barometers of trends, not individuals making their own way and expanding the expression of human intricacy as they move. Just as Bill Cosby’s television show decries the limitations of buffoon humor, opting for an artistry as down-home as it is universal, Marsalis wants to make music in keeping with the world-spirited joy and seriousness of Armstrong, Ellington, Parker, Monk, Coltrane, and the best of Davis, Coleman, Shorter, and Hancock. In his mind, the pressure of commercialism is another form of Black Codes, one that reduces all willing musicians to highly paid but low-grade plantation entertainers, regardless of race or idiom. The late Roland Kirk called it “volunteer slavery.” Coming from the other side of the field, Marsalis is more interested in the statement than the payment.

The first obvious level of statement is the leader’s development as a composer. Each of the pieces is written differently, has its own mood, and reveals an individual emerging through the influences that are immediately obvious. “In every era you have composers who stand out and who set up directions. Ellington and Strayhorn tower over everybody. Then you have Monk. Then Wayne Shorter. Right now, it is easy to see that Wayne took the music in a fresh direction because of his organic conception of the interaction of melody, harmony, and rhythm. Some of the avant-garde composers wrote interesting lines, but I haven’t been impressed by their harmonic ideas. Wayne Shorter knows harmony perfectly and, just like Monk, every note and every chord, every rhythm, every accent–each of them is there for a good reason.”

Beyond the impressive skill exhibited in the odd structures of the writing, there are improvisations of such conscious order, fire, and rhythmic fluidity that the combination of individuality and continuity gives each piece the feeling of a whole because each musician so decidedly uses what has been played before him as he makes his own statement, the compositions never stop and are always more than strings of so-called solos. Above it all, however, is the swing and the lyricism. The leader has never played this well on record. There is the clarion melancholy of his superbly controlled work on the title tune, the breezy relaxation of “Delfeayo’s Dilemma,” the puckish snarls of “Phryzzinian Man,” the raw force and structure of “Chambers of Tain,” and the sublime flutters of his ballads. Branford Marsalis, like his brother, has absorbed many ways of swinging, from shifting molten rhythms to the way he sweeps Lester Young’s coolness and detached elegance into contemporary harmony on “Phryzzinian Man,” moving from a superb variation on the brief interlude that introduces him into a creation that is absolutely melodic. Kenny Kirkland not only accompanies each horn with different colors, attacks, rhythms, and meters, but proves that there is no pianist under 40 in jazz who can swing harder, invent with more linear control, or execute such supple rhythms. Seventeen-year-old Charnett Moffett is shocking in his swing and his sound, never losing his place as Kirkland and Watts reorder the accents and superimpose other time signatures. Ron Carter, as usual, does an impeccable job in reinterpreting and developing the thematic structures and harmonic ideas presented in “Aural Oasis.” Then there is Tain (“What’s Your Name?” “Puddin’ and Tain, ask me again and I’ll tell you the same.”): probably the dean of the younger drummers, as the ballads show, he is already a master of cymbal timbre, and the swing he pulls off by periodically accenting his sock cymbal on the second half of two and four or effortlessly adjusting when other meters are introduced, prove him a man of remarkable instincts and attentiveness to detail. Most importantly, his playing is in the tradition of the hot heart of polyrhythm Elvin Jones perfected.

In all, this recording is a testament to the craft, integrity, and passion that idealism instigates. We are all lucky that such young musicians are playing jazz and handling its greatest demands with such an emotive sense of order. This is an eloquent attack on the contemporary definitions of Black Codes, which the leader explains with direct insight: “Black Codes mean a lot of things. Anything that reduces potential, that pushes your taste down to an obvious, animal level. Anything that makes you think less significance is more enjoyable. Anything that keeps you on the surface. The way they depict women in rock videos–Black Codes. People gobbling up junk food when they can afford something better–Black Codes. The argument that illiteracy is valid in a technological world–Black Codes. People who equate ignorance with soulfulness–definitely Black Codes. The overall quality of every true artist’s work is a rebellion against Black Codes. That’s the line I want to be in–and definitely have plenty of examples.” In fact, young Mr. Marsalis, you are quite an example yourself.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

1. Black Codes

(W. Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

2. For Wee Folks

(W. Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

3. Delfeayo’s Dilemma

(W. Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

4. Phryzzinian Man

(W. Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

5. Aural Oasis

(W. Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

6. Chambers of Tain

(K. Kirkland) Kenny Kirkland Music

BIEM/STEMRA

7. Blues

(W. Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

MUSICIANS:

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet)

Branford Marsalis (tenor and soprano saxophone)

Kenny Kirkland (piano)

Charnett Moffett (bass)

Jeff Watts (drums)

Ron Carter (bass on “Aural Oasis”)

Recorded At RCA Studio A on January 11th and 14th, 1985

Chief Engineer: Tim Geelan

Assistant Engineer: Dennis Ferrante

Additional Technical Assistant: Delfeayo Marsalis

Remixed at CBS Recording Studios, NYC

Remix Engineer: Tim Geelan

Mastered At CBS Recording Studios By Vlado Meller

Recorded Digitally using the Sony PCM 3324 Digital Recorder

Principal Microphones: Neuman: U-67, KM-84. T170i, AKG: 414EB-P-48,451

Monitor Speakers: B&W 801

Recording Console: MCI

Remix Console: Neve Automated Console

Management: Edward C. Arrendell

Arrendell Management Group

P.O. Box 55398

Washington, D.C. 20040

Art Direction: Mark Larson

Photography: Gary Heery

Special Thanks To: George Butler, Vernon Hammond, Vernon Slaughter, Genevieve Stewart, Billy Banks, Mrs. Dolores Marsalis, Delfeayo Marsalis, Jason Marsalis. Steve Epstein, Tim Geelan. Mark Larson, Holly Henley, and Donna Kresel.

Personnel

- Charnett Moffett – bass

- Ron Carter – bass

- Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums

- Branford Marsalis – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Kenny Kirkland – piano

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Delfeayo’s Dilemma - Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Ronnie Scott’s 2013

-

Videos

Videos

Black Codes - Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Ronnie Scott’s 2013

-

Videos

Videos

Phryzzinian Man - Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Ronnie Scott’s 2013

-

Videos

Videos

Aural Oasis - Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Ronnie Scott’s 2013

-

Videos

Videos

Black Codes - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Berlin (1989)

-

Videos

Videos

Black Codes - Wynton Marsalis Sextet at Newport Jazz Festival 1989

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis reflects on the way time flies, as Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra plays a program full of his work

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis Is Focus as Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra Opens Season