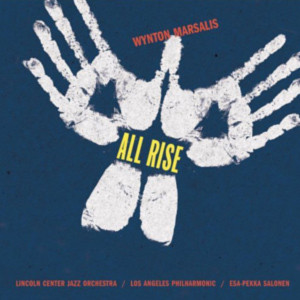

All Rise

ALL RISE is an extraordinary, massive work on the scale of Marsalis’ 1997 Pulitzer Prize-winning oratorio BLOOD ON THE FIELDS. Performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra and a 100-voice choir, ALL RISE reaches across styles and genres, from jazz and blues to classical and world music.

All Rise was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and premiered at Lincoln Center in December 1999.

Album Info

| Ensemble | JLCO with Wynton Marsalis and the Los Angeles Philharmonic |

|---|---|

| Release Date | October 1st, 2002 |

| Recording Date | September 14-15, 2001 |

| Record Label | Sony Classical |

| Catalogue Number | SK 89817 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz at Lincoln Center Recordings |

| Digital Booklet | Download (pdf, 3 MB) |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| CD 1 | ||

| Jubal Step | 11:22 | Play |

| A Hundred and a Hundred, a Hundred and Twelve | 7:52 | Play |

| Go Slow (But Don’t Stop) | 9:00 | Play |

| Wild Strumming of Fiddle | 8:13 | Play |

| Save Us | 10:24 | Play |

| Cried, Shouted, Then Sung | 8:39 | Play |

| Look Beyond | 9:05 | Play |

| The Halls of Erudition & Scholarship | 10:00 | Play |

| CD 2 | ||

| El ‘Gran’ Baile de la Reina | 7:38 | Play |

| Expressbrown Local | 6:41 | Play |

| Saturday Night Slow Drag | 5:24 | Play |

| I Am (Don’t You Run From Me) | 11:53 | Play |

Liner Notes

Those virtuoso musicians who know and love music, and have played many, many kinds of it, have something special in common. They always know – without a doubt – when they have been part of a major event. They are very clear on the actual point at which new artistic ground has been taken, when assumed impossibilities have become possible, when the aesthetic vista has been broadened. Such musicians are the ultimate insiders, the ones hardest to please, the members of the music world most ready to complain to one another about the dreck they had to play for such and such occasion. Not only are they ready to make jokes about a movie score or giggle about the mediocre talents they have had to accompany, these kinds of professionals are also ready to speak dismissively of things that they might even respect for their technical brilliance. That is because such musicians are not moved by even highly accomplished music that does not contain fundamental qualities that they have discovered in every great work they have played, regardless of the era or the style in which it was written.

When the last note of this recording was played, many members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic spontaneously lined up in order to individually tell Wynton Marsalis how marvelous a piece he had written and how much they had loved playing it. There you go and there it is. Serious praise of that sort is an unusual thing for a composer to receive in our time, since orchestra musicians very, very rarely talk of enjoying or loving some new music, or even feeling that it actually is new.

As Bob Karon, an auxiliary trumpet player with the L.A. Philharmonic observed, “First of all, the Lincoln Center band sounds unbelievable. It’s great to hear them play; everyone is a terrific soloist, and they’re also great ensemble players. So it’s very inspirational to listen to that wonderful playing. The other thing is that Wynton has the orchestra fit with the jazz group, and the choir. I love the way he uses everything, all these wonderful sounds.”

“I’ve been around the L.A. Philharmonic for thirty years, and there’s a lot of sounds I have never heard come out of an orchestra before that he was able to create. So his ideas about orchestration are great. Somebody said the other day, This is the hippest thing the orchestra has ever done,’ and I really think that’s true. It’s very exciting to be a part of it.”

What so impressed the musicians of the L.A. Philharmonic as players is, clearly, the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, which, in the words of Loren Schoenberg, “sets a new standard for Jazz performance.[It is] an ensemble matched only by the great bands of yesteryear.” The other thing is that the music itself expands upon what Schoenberg observed about the composer in The Curious NPR Listener’s Guide to Jazz: “Marsalis’s music transcends the artificially induced demarcations of “style” that tend to divide the Jazz world, by arriving naturally at a synthesis of the music’s past and present that has an essentially inclusive feeling to it.”

The most important inclusive aspect of any work of art is its human quality. That is what violinist Lawrence Saunderling, a twenty-five year veteran of the L.A. Phil, addressed when asked what the music meant to him as an American playing America’s music, “It means a great deal to me because this is music that touches people. It’s not something that’s cerebral, or intellectual alone. It has an intellectual basis, but it’s also music that people feel, that the musicians feel. Music isn’t music if it doesn’t involve you; if you’re here and the music is over there, then there’s no meaning to it. This is something that everybody feels; the jazz orchestra feels it; we feel it; the singers feel it; and the music is for people to feel and become a part of, whether they’re playing it or listening to it. We have a major piece of music now that people can feel like they’re a part of.”

Finally, Boyde Hood, a trumpet player who has been with the Los Angeles Philharmonic for twenty years, speaks of this work as it compares to the many orchestra pieces he has performed by twentieth century composers, “I think this piece is certainly one of the best, from a lot of vantage points. It’s one of the best because of the intent of the piece. The idea of always striving and rising above adversity, that kind of thing.”

“But I think if it doesn’t work on the musical level, then whatever the emotional intent is doesn’t work as well, because you’re hampered as a listener, or as a performer, with the fact that some piece might not be a very good piece. In this case, it’s a sensational piece. I mean it’s really a wonderful piece of music, so the message that he’s trying to get across is enhanced by the fact that you’re enjoying what you’re listening to. Therefore, the music takes you even further. What he’s managed to do, because he’s such a wonderful; musician, is take all these disparate elements, from Stravinsky to Gospel, and make them work in this setting. I don’t know if you would call it a “third stream” type of thing, because it’s more than just a fusion with jazz. It’s taking all of the elements of the musical language and making them work within a piece of music. And that’s very different from just classical and jazz when you put it all together. He’s taken all this varied musical language that we have as composers and performers and has made it work as a single piece of music, without being self-conscious about it. And that’s what I find to be really extraordinary.”

So what we have, if we step back into our common heritage, is a musical expression of “E Pluribus Unum” – “out of many, one.” We hear music that takes us around the world in twelve movements and brings with it many associations, but the central force arrives from the Negro American idioms of folk song, ragtime, blues, Spirituals, Gospel, New Orleans jazz, and the jazz that expanded upon what was discovered down there on the Mississippi in the Crescent City. That Negro American vitality, at its very best, is one of the truest beacons of human hope, for it tells us all, repeatedly, that we need not be reduced to the interior condition of savage beasts due to great suffering. Though we might get brutally knocked down, over and over, getting up is the highest identity of the human species. All rise.

– Stanley Crouch

The 20th was the century of communication. The 21st will be the century of integration. Our rapidly developing global community is the most exciting modern reality. But to the first jazz musicians in New Orleans, Louisiana, some 100 years ago, the global village was already real. Pianist and composer Jelly Roll Morton said, “We had all nations in New Orleans, but with the music, we could creep in closer to other people.” Today the world is so small, we don’t need music to creep in closer to other people: we are close. The larger question of this moment is how will we translate our differences into a collective creativity? That’s where the blues comes in. The blues in an approach to harmony, a way of rhythm and a body of vocal textures sung through horns. It’s a melodic attitude featuring minor in the major mode and major in the minor mode, the pentatonic scales of Eastern music, the quarter tones and altered scales of Near and Middle Eastern music. The blues is call and response, as well as the high shuffle of a cowbell in some thick African drum stretto. But mostly, it is an attitude towards life, celebrating transcendence through acceptance of what is and proceeding from there in a straight line to the nearest groove. With the blues you got to give some to get some.

All Rise is structured in the form of a 12 bar blues. It is separated into three sections of 4 movements. Each section expresses different moments in the progression of experiences that punctuate our lives. It is a personal and communal progression. The first four movements are concerned with birth and self-discovery; they are joyous. The second four movements are concerned with mistakes, pain, sacrifice and redemption. They are somber and poignant. The last four are concerned with maturity and joy. All Rise contains elements of many things I consider to be related to the blues: the didgeridoo, ancient Greek harmonies and modes, New Orleans brass bands, the fiddler’s reel, clave, samba, the down home church service, Chinese parade bands, the Italian aria, and plain ol’ down home ditties. Instead of combining many different styles on top of a vamp, I try to hear how they are the same. In attempting to unite disparate and large forces, everyone has to give up something in order to achieve a greater whole. The jazz band has to play more 2/4 marches and ostinato bass grooves, while the orchestra has to adapt to a percussive roughness and the metronomic dictates of a rhythm section. The choir must do lots of waiting. The fun is in the working together.

1. JUBAL STEP

We are created in joy and we love to create. The main theme is a little riff my great Uncle Alfonse, who was born in 1883, used to sing to me when I was boy.

This movement is a march. Jazz, ragtime, the fiddler’s reel, and most South American dance rhythms are connected through the march. The men sing “Ah Zum,” to mean from the beginning to the end in one instant, and then we begin. The “Ah” also means “and,” as if to say our beginning is a continuation. Soon everything starts spinning and then the families (strings, woodwinds, percussion, etc.) dance together. In the introduction, the jazz band plays small samba drums called tambourin and progresses from elemental syncopation to an involved Latin rhythm called “cascara.”

The harmonic direction is ambiguous. It could be in F major or C dominant or D minor. In the middle vocal section the men sing “M-m-m-m” as if calling for their mothers, and the women sing “Da-da-da-da-da” as if calling for their daddies. The orchestra is in F Dorian while the choir sings blues in E flat and C.

Because every march must have a trio, there is a trio section for flute, bassoon and clarinet. Then the jazz band enters on an A flat dominant 7 chord, implying minor blues in the key of C. The orchestra returns for what will be an extended coda featuring African inflected moving bass with open orchestral chords, a syncopated blues riff in the jazz band and the “cascara” rhythm in the percussion.

2. A HUNDRED AND A HUNDRED

The joy of play.

This is based on a little chant my son Simeon sang for about two hours on a train ride. It begins in the key of C sharp major and ends in D flat major with many modulations in between. It is a form of danzon that utilizes what we call New Orleans clave. It features juxtaposition of the low and high registers and a repeated teasing theme with wa-wa trumpet or trombone. It also has samba and bossa nova rhythms, as well as a type of counterpoint that comes from New Orleans jazz.

3. GO SLOW (But Don’t Stop)

From the cradle to the grave everyone loves love. Getting it and giving it.

The form of this movement follows the process of emotional maturation in romantic matters. The opening waltz is naïve and adolescent. It is a pastoral folk theme which progresses down a cycle of fourths from D to A to E to B to F sharp to C sharp to A flat major. The jazz band orchestra enters in the key of A flat with an unusual type of integrated harmonic voicing. This section is sensuous, adult and active. It culminates in a piano solo that features six bar phrases. The last section combines the jazz and symphonic orchestras in a typical jazz-with-strings type format plus a few unusual blues twists. This last rung of the romance is wistful and aged.

4. WILD STRUMMING OF FIDDLE

We discover we can do wonderful things, get the big head and get lost in a labyrinth of our own magnificence.

This movement is the country fiddle with well-rooted bass in the key of A major. It questions whether the American school of fiddle playing, simpler in harmony but stronger in groove, should not have received more attention form American composers. Each section – violins, violas, cellos and bass – is introduced one at a time before the main theme enters. The wild strumming on open strings is full syncopated juxtaposition with the bass utilizing melodic fourths found in some types of African music and the treble using the open string scrapings of the country fiddle. I used three different modes of exposition in this movement: 1) the chorus format of jazz and all-American popular music, 2) fugue, and 3) a groove in the African six-eight clave which is stated by trumpet and horns.

5. SAVE US

We mess up.

No use to beg, but the name of the Lord will be found on everybody’s lips in times of crisis. The drums of war recycle the relationship of a battalion of Brazilian tambourin in call and response with a battery of percussion. The cowbell articulates the African six-eight clave. An alternating vamp of five-four and six-four in the key of F minor leads to a new harmonic progression and groove, in the style of John Coltrane. On top of this groove is a string counterpoint led by two saxophones. Two trombones improvising presage the funeral procession in the next movement. Then we hear a different concept of the blues harmony with the teeming choir against the solo cries of “Save us” and “For we know not what to do.” The choir uses a fragment of the fugal theme from movement four to express “Help us, oh Lord.” A trumpet solo in response to the cries of “Save us” declares “Permission denied.” Then the brass slaps with saxophone scurrying; this evokes the scrambling that goes on whenever the bright light of justice is shone on dense segments of willful darkness. Wess, in his inimitable style, ends this movement with a soulful cry.

6. CRIED, SHOUTED, THAN SUNG

We suffer. After crying for denied mercy we move on to death.

This movement begins with the New Orleans funeral that is always initiated by the solo trombone. Vic provides the proper Crescent City filigree on his clarinet. We then progress to the English Brass Choir, followed by the solo violins – all in mourning, the first signs of healing. The reverend shouts a sermon in the tradition of the Afro-American church. The tuba preaches, the French horns are the choir, the jazz trumpet is a sister in the back of the church, and the jazz trombone of Ron Westry is the elder deacon and chief co-signer. After the sermon the choir sings of the arrogant and self-aggrandized viewpoints that always lead to gross inhumanity in the name of God and in the name of Jesus. This movement progresses from C minor to F major to D minor to A minor. To A something or another.

7. LOOK BEYOND

We ask forgiveness and are redeemed.

After some introductory passages, the pastoral main theme is stated by bass, then cello, then viola. Each statement is answered by bass, clarinet and alto saxophone of the jazz band. With each reiteration the theme becomes more syncopated under the influence of a washboard-inflected groove. The washboard is the folk element of the blues that cannot be corrupted. It represents the strength to resist over-refinement and willful descent into ever more elite forms of intellectual masturbation that often replace basic human engagement. A washboard puts you right in the laundry room where souls are cleansed and replenished. “Look beyond” means look past what you have been taught, what you want, what you feel. Beyond what is expected. Beyond all judgment – to what you know. This is sung to a backbeat which represents under-refined forms of human engagement that preclude the type of thought, sophistication and feeling that enriches civilization. We look beyond that static groove to the fluid motion of swing. This movement progresses through the keys of A flat major, F major, G major and D dominant.

8. THE HALLS OF ERUDITION AND SCHOLARSHIP (Come Back Home)

We are forgiven and welcomed home.

This movement features the brass and percussion. In the first movement everything spins. Here, the brass bounces and throbs with the same motion and basic melodic structure. The low brass appear periodically in a “God’s trombones” type of response derived from Afro- and Anglo-American folk music. This piece stays in the key of F major because once you get home there’s no place else to go. The brass, woodwinds and strings say their piece and the jazz orchestra returns again and again to repeat the same phrase, “Welcome Back Home.” A Printupian trumpet solo further clarifies “Welcome” because to swing means to welcome. In the end the choir comes from the contemplative space of suffering and resolve that produced the majestic Negro Spirituals.

9. EL GRAN’ BAILE DE LA REINA

We are reborn in joy.

The deepest expression of joy short of spiritual rapture is romance. And romance’s calling card is dance. This movement is an integration of various types of Latin dances, from Argentinian Milonga to Afro-Cuban Mambo. There are periodic rubato solo sections for the man (cello) and woman (violin) to work things out. We end with a big coda in the style of the large South American dance orchestras.

10. EXPRESSBROWN LOCAL

Who doesn’t love trains? From the toy train to the express train to the bullet train to John Coltrane.

The train also has symbolic significance for the Afro-American. From Duke Ellington’s “Track 360″ to Aaron Copland’s “John Henry,” the train is freedom and power. Train tracks often delineate black and white neighborhoods in the south. The Underground Railroad was the Freedom Train. The Gospel Train is the Glory Train. The basic shuffle of the blues is the chugging of engine and wheels. The cries, shouts and exhortations of horns are many, many train whistles tooting at will. Even the complicated lines of bebop have a relationship to the big country swing of the Western train. Charlie Parker was from Kansas City. They know about trains there.

11. SATURDAY NIGHT SLOW DRAG

The slow blues – unsentimental romance, wise love, a dance, an attitude, a modality.

The slow drag – vertical expression of the most salacious horizontal aspirations.

Saturday night – when things that should be confessed on Sunday take place.

12. I AM (Don’t You Run From Me)

Sunday morning. God’s love calls us to rise to the complete fulfillment of who we are. We choose how high and how soon. From the I AM of materialistic self-aggrandizement to the great I AM of brotherhood, sharing and love. There is no greater journey or battle for individuals or groups. The act of rising is itself thanks for God’s love which is the source of all life and creativity.

All Rise was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and Kurt Masur as the last of the millennial compositions of 1999. This piece for me was the culmination of a ten-year odyssey during which I sought to realize more complex orchestrations for long form pieces based in American vernacular music and jazz.

I devoted every single day of 1999 to working on composition, recording and performance in gratitude to my many friends, fans and colleagues around the world for the more than many wonderful experiences I have enjoyed in my 20 years of playing. I wanted to give thanks to God and reaffirm my commitment to continued creativity. In this year, fourteen diverse recordings were released; new arrangements for big band and symphonic orchestra of four Duke Ellington pieces including “A Tone Parallel to Harlem” were completed; the LCJO conducted a year-long celebration of Ellingtonia with 70 performances across the US and Europe; a new ballet, “Them Twos” (my first composition for orchestra) was performed by the New York City Ballet; and ultimately, All Rise was premiered at the end of December. All Rise required a notebook full of structural details and written thematic relationships. James Oliverio and teams of copyists were exhausted, and Victor Goines copied jazz band parts through his Christmas holiday.

After the NY Philharmonic premieres on December 29 and 30, 1999, it took six months for me to recover. The last thing I wanted to hear or think about was this piece. The next performance took place in Prague with the Czech National Orchestra conducted by Vladimir Valek in October of 2000. The audience response was overwhelming.

In February 2001, I sent a score and recording of this performance to Esa-Pekka Salonen. Some 18 years earlier Esa-Pekka and I had recorded an album of trumpet concertos. Through the years we maintained a very high level of professional respect for one another. He agreed that we would perform All Rise with the Los Angeles Philharmonic on September 13, 2001. Because we are both Sony Classical artists, we felt that with proper negotiations a recording would be possible. With much strategizing and calling on friendships and professional relationships, The Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Morgan State Choir from Baltimore under Nathan Carter, the Paul Smith Singers and the Northridge Singers of California State University at Northridge all came together to perform and record All Rise. Many of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s senior management came out for the event, and a truly warm feeling surrounded our first rehearsals.

The came the attacks of September 11th. Jazz at Lincoln Center Director of Publicity Mary Fiance Fuss called to tell me a plane had flown into one of the twin towers. As we watched the news, we caught the second plane hitting the second tower. Within minutes everyone in the band was on the phone. Later that day, a meeting was called to discuss what to do. The decision was unanimous: stay and play. Our next rehearsal was made forever memorable by the outpouring of concern and love from the members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Initial portions of our September 13th concert appeared on CNN; the station broke from Ground Zero coverage to broadcast our joint performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The performance, though justifiably somber, was energetic and meaningful.

The recording was another issue. Due to the suspension of national air travel, our producer, Steve Epstein, perhaps the only person in the world with the experience to make a quality recording of such large and diverse musical forces, was stranded in Kansas City. And our engineer, Todd Whitelock, was stranded in Detroit. With the recording scheduled for September 14th, we were in trouble. As we were about to cancel the recording, several uncommon acts of dedication saved the sessions. A close personal friend and colleague, “Boss” Dennis Jeter, was driving from Los Angeles to New York to tend to a family crisis. When called, he drove to Kansas City and brought Steve Epstein to Rifle, CO, where our road managers, Raymond “Big Boss” Murphy and Eric Wright, were waiting to drive Steve on to L.A. Rodney Whitaker, our bassist from Detroit, called Koli Givens, a trumpeter and close personal friend. Koli and his cousin, Quintin Givens, drove non-stop from Detroit to L.A. and delivered our engineer. Even though time was limited and the recording schedule was tight, a deeper sense of community and inspiration guided us through these sessions.

After the recording the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra was scheduled to play Benaroya Hall in Seattle, WA. We drove 27 non-stop hours by bus directly from the session to the stage. Waiting for us on the bus were pillows and blankets for the entire band provided by Evan Wilson (violinist, Los Angeles Philharmonic) and his family, a gesture of friendship and love that will forever remain with the LCJO. Our concert was scheduled to begin at 7:00 p.m. – we entered the city limits at 7:00 p.m. Out on the stage we received an extended standing ovation from a sold-out house that had waited patiently to be, in the words on one patron, “reminded of who we are.” The LCJO was back on the road. We heard that some acts chose to cancel their tours following September 11th. We chose, and still choose, to swing.

– Wynton Marsalis

I. JUBAL STEP

Ah Zum.

II. HUNDRED ANO HUNDRED, HUNDRED ANO TWELVE

A hundred and a hundred, a hundred and twelve.

A hundred and a hundred, a hundred and twelve.

A hundred and a hundred, a hundred and a hundred,

and a hundred and twelve.

V. SAVE US

(General hollering and sounds of discomfort, chaos and angst)

Comfort me, comfort me

Save us, O Lord

For we know not what we do.

Help us, O Lord

For we know not what we do.

O Lord, have mercy on us.

Please Lord, please Lord

Mercy, mercy

Forgive me.

Save us, O Lord

For we know not what we do.

Help us, O Lord

Set me free.

VI. CRIED, SHOUTED, THEN SUNG

Our fellow man,

Break him up, where him stand,

Slap away him open hand.

Steal him gold and take him land.

Then give him Jesus.

Jesus, save him soul, Jesus.

Oh cry his children,

Hear them cry aloud.

So, mock our children, hear them

Sanctify the lies we’ve sold.

And that same Jesus

Come to save our souls.

Ride on, King Jesus.

Teach us to be

Our fellow man,

In him in me,

All sing freedom, freedom.

Let it ring, freedom,

Was always is and will be.

Oh Freedom, freedom, freedom.

In the name of Jesus be. Beyond.

VII. LOOK BEYOND

Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.

Almighty God, Thy love is forever healing.

Hosanna in the highest. All glory in Thy holy name. Hosanna.

Look beyond, look beyond.

Beyond

VIII. THE HALLS OF HERUDITION AND SCHOLARSHIP (COME BACK HOME)

Raise your hands and praise the Lord. Hallelu.

Raise your voice and praise the Lord, O Hallelu.

Raise your hearts and feel the Love of our God.

Let God be what He is in you.

Little David come play your harp,

And the angels sing.

I hear Gabrielle a-blowin’ her horn.

Baa-bee-doo-bee, doo-bee

Baa-bee doo-bee-doo

Baa-doo-bee doo-bee doo-bee

God is calling us. “Come back home.”

You keep on knockin’ but you won’t come in.

You keep on walkin’ past the house He’s in.

He’s always home, don’t you mind what they say,

And not one soul is ever turned away.

Yes, the Lord’s always here to hold our hands.

And He say come back home.

Come by Lord, come by Lord.

Hear me prayin’ won’t you come by Lord.

In my deep sorrow did our Lord appear.

A song He giveth me to calm my fears.

Come by Lord, come by Lord.

Hear me prayin’ won’t you come by Lord.

In His song my soul abides.

In every cry and joyous shout,

I AM PRESIDES.

We offered You our song to harmonize.

Our song, healing.

Come by Lord, come by Lord,

Hear me prayin’, won’t you come by Lord.

O my Lardy, won’t you come by here,

O sweet Jesus, won’t you come by here.

Save our souls, Lardy, save our souls,

Save our souls, Lord, save my soul.

Hear me prayin’ won’t you come by Lord.

Bleed my song till it sings untrue,

Still I’m gonna sing my song in blue.

Glory train coming through.

Help us Lord sing our souls, sing our song.

Yes the Lord’s always here to hold our hands.

And He say come back, and He say come back,

And He say come back home.

XII. I AM (DON’T YOUR RUN FROM ME)

I say All Rise,

And be heard.

And now All Rise,

Choose to be.

Oh, hear the cry of God’s sweet love

Call to be who you are.

All choose, all see, all rise, all be, the love of God,

To praise His name.

All Rise, All Rise, give thanks for all life.

Zurn, zum, zum, I am, I am, I am.

Thy will be done.

Lord, comfort me.

I am. All Rise.

For the glory of God.

Thy will be done, Lord comfort me.

Look beyond, look beyond, higher.

Look higher, look higher and higher

I am.

Look beyond.

All Rise.

Listen up and hear me sing my song

I’m a-sing it loud and long.

Oh! And don’t you think that you can feel my song

Lest you comfort me.

You runnin’ around, oh you grabbin’.

Wantin’ to buy everything you see.

What’s bought won’t make you be.

Oh. why don’t you tell me

Why you keep on pushin’ me ‘round

And knockin’ me down.

Can’t you see that I’m gonna rise and rise and,

Oh yes! Our Lord has given us all

Something that just refuses to die

Open your heart and see,

Then you’ll hear the sweet soul

Of what I sing.

It’s for you and for me.

Oh, don’t you run, baby don’t you run,

Don’t you run from me.

Credits

SOLOISTS FROM THE JAZZ BAND

Movement I

Wess Anderson, alto sax

Movement II

Walter Blanding Jr., tenor saxophone

Ted Nash, piccolo

Movement III

Peter Martin, piano

Movement IV

Rodney Whitaker, bass

Movement V

Vincent Gardner, 1st trombone solo

Ronald Westray, 2nd trombone solo

Wynton Marsalis, trumpet

Movement VI

Victor Goines, clarinet

Norman Pearson, tuba

Movement VII

Peter Martin, piano

Movement VIII

Marcus Printup, trumpet

Movement IX

Joe Temperley, baritone sax

Ryan Kisor, Marcus Printup, Seneca Black, Wynton Marsalis, trumpets

Movement X

Ted Nash, alto sax

Wess Anderson, alto sax

Ryan Kisor, trumpet

Movement XI

The LCJO

Movement XII

Ted Nash, flute

Jason Marsalis, drums

VOCAL SOLOISTS (in order of appearance)

Movement V

Cynthia Hardy, Alto

Kenneth Alston, Tenor

Kevin McAllister, Baritone

*Elliott Jackson, Baritone

Movement VIII

Miriam Richardson, Mezzo Soprano

*Elliott Jackson, Baritone

Issachah Savage, Tenor

Kenneithia Redden-Mitchell, Soprano

Sequina DuBose, Soprano

Movement XII

Cynthia Hardy, Alto

*All soloists from Morgan State Choir with the exception of Elliott Jackson from the Paul Smith Singers.

SPECIAL THANKS TO:

Jason Marsalis, for coming through on such short notice

Rob Gibson

James Oliverio, for invaluable assistance and advice on musical matters

Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic

Dr. Nathan Carter

Paul Smith

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Steven Epstein

Todd Whitelock

Peter Gelb

Paul Geller

Calvin Hunt

Randa Kirschbaum

Jonathan Kelly

John Miller

Mark Pachucki

Dennis Jeter

Bob Sadin

Miri Ben Ari

Victor Goines

Koli Givens

Quintin Givens

Eric Wright

Big Boss Murphy

Peter Martins

Genevieve Stewart

Ricki Moskowitz

Kierstan Smith

Nathan George

WYNTON MARSALIS, trumpet

The Paul Smith Singers

The Northridge Singers of California State University at Northridge

(Dr. Paul Smith, director)

Morgan State University Choir

(Dr. Nathan Carter, director)

Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Producer: Steven Epstein

Recording and Mixing Engineer: Todd Whitelock

Editing Engineer: Robert Wolff

Assistant Engineers (Todd A-0): Jay Selvester, David Marguette

Technical Supervisor (Todd A-0): Mark Gebauer

Digitally recorded in 24 bit resolution at Todd A-0 Scoring Stage, Los Angeles, CA, September 14-15, 2001.

Edited and Mixed at Sony Music Studios, NYC

A&R Manager: Ruth DeSamo

Product Manager: Bob Kranes

Editorial Production: Elliott Media Services Inc,

Art Direction and Design: Giulio Turturro

Photography: Frank Stewart

All Rise was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and premiered at Lincoln Center on December 29-30, 1999

All compositions written by Wynton Marsalis (Skayne’s Music/ASCAP)

www.esa-pekkasalonen.com

www.sonyclassical.com

The Management Ark

Edward C. Arrendell II • Vernon H. Hammond III

ALL RISE lyrics © 2000 by Wynton Marsalis Enterprises, Inc.

All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

© 2002 Sony Music Entertainment Inc. / ℗ 2002 Sony Music Entertainment Inc.

This CD utilizes Sony’s DIRECT STREAM DIGITAL (DSD) System and SBM Direct.

Digitally recorded in 24 bit resolution.

Personnel

- Paul Smith Singers – vocals

- Esa-Pekka Salonen – conductor

- Morgan State Choir – vocals

- The Northridge Singers of California State University at Northridge – choir

- Peter Martin – piano

- Jason Marsalis – drums

- Rodney Whitaker – bass

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Walter Blanding – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet

- Ted Nash – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute, piccolo

- Vincent Gardner – trombone

- Ron Westray – trombone

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Joe Temperley – baritone sax, bass clarinet

- Ryan Kisor – trumpet

- Seneca Black – trumpet

- Marcus Printup – trumpet

- Norman Pearson – tuba

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton Marsalis on Black Wall Street and ‘All Rise’ with the Tulsa Symphony - DC Today BNC

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton Marsalis discusses about “All Rise” performance in Tulsa - KOTV News On 6

-

Videos

Videos

El ‘Gran’ Baile de la Reina - Nutcracker Swing (Part 5)

-

Videos

Videos

Expressbrown Local - Nutcracker Swing (Part 4)

-

Videos

Videos

Wild Stumming of Fiddle - Nutcracker Swing (Part 3)

-

Videos

Videos

Go Slow But Don’t Stop - Nutcracker Swing (Part 2)

-

Videos

Videos

Intro with Leonard Slatkin - Nutcracker Swing (Part 1)

-

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

The JLCO with Wynton Marsalis performing “All Rise” with Sydney Symphony Orchestra in Sydney (performance #2)